cliftonWONG

A scholar bridging cities and care through transdisciplinary approaches. I study how urban systems and spatial design can cultivate compassion.

Clifton Wong

Hi! I am focused on improving the liveability and equity of urban spaces.

Early in my career, my role as a Project Architect took me to construction sites in Singapore and Australia, building technical depth and management capabilities.

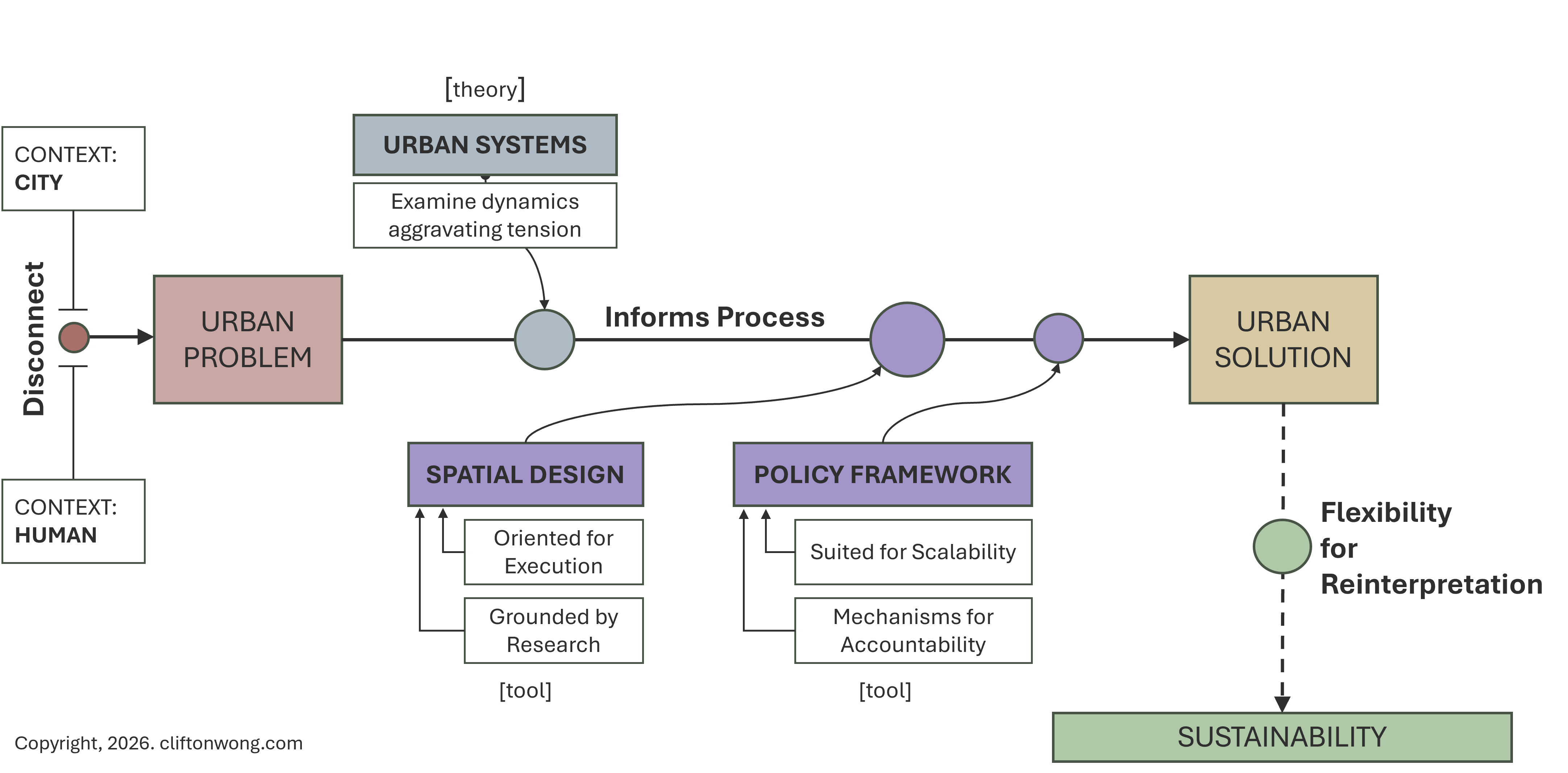

Now, with my Construction, Urban Science and Law background, my work operates at the intersection of Urban Systems, Constructible Architecture Design and Legal Policy, examining how urban problems and their solutions are framed and translated from theory to application, and how urban tools like design and policy mediate that process.

-

A few places my work has taken me:

-

Expertise in Urbanism, Architecture and Law.

-

Building Public Housing in Singapore.

-

Developing Resorts in Australia.

-

Teaching Architecture & Economics.

-

Fellowship with CIArb and SIArb.

-

Dabbling in writing and sketching.

Building Projects

- Lindeman Island Resort

- Queensland, Australia

- Mantra Club Croc Airlie Beach

- 240 Shute Harbour Rd, Australia

- Queen's Arc

- 200A Queen's Crescent, Singapore

- Forest Spring

- Yishun Avenue 1, Singapore

Teaching Experience

- SMU-X | Gametize x Moral Home for the Aged Sick

- SMU, Industry Mentor with Dr. Rani Tan

- AR2524 | Spatial Computational Thinking

- NUS, with Dr. Patrick Janssen

- AR2723 | Strategies for Sustainable Architecture

- NUS, with Dr. Yuan Chao

- GCE H2 Economics

- Private

Education

- MSc. in Urban Science, Policy and Planning

- SUTD

- Graduate Certificate in International Arbitration

- NUS

- Bachelor of Arts (Architecture) (hons)

- NUS

- Bachelor of Laws (hons)

- UOL

Scholarships & Awards

- Azimuth Labs - SUTD LKYCIC Scholarship

- For the degree of MSc. USPP

- Board of Architects Prize & Medal (Silver)

- For the degree of B.A. (Arch)

- Dean's List AY2020/21

- For the degree of B.A. (Arch)

- Milton Tan Best Progress Award AY2018/19

- for the degree of B.A. (Arch)

- Direct iBuildSG Undergraduate Scholarship

- For the degree of B.A. (Arch)

- TAS Inter-varsity Debate (2018)

- Winning Team, Best Speaker

Activities & Memberships

- Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (CIArb)

- Fellow (Current)

- Singapore Institute of Arbitrators (SIArb)

- Fellow (Current)

- Built Environment (BE) Young Leaders Programme

- Programme under Building & Construction Authority (2022 - 2023)

- Kidzcare Homework Club

- Volunteer Tutor for underprivileged children (2016 - 2019)

Digital Skills

- Computer Aided Design

- Rhinocero3D, AutoCAD

- Parametric Design

- Grasshopper, Mobius Modeller

- Building Performance Simulation

- Butterfly (CFD), Ladybug (Radiation), I-SIMPA (Acoustics)

- Programming Language

- R, Python

- Graphic Design Software

- Illustrator, InDesign, Photoshop

Curated Selection

-

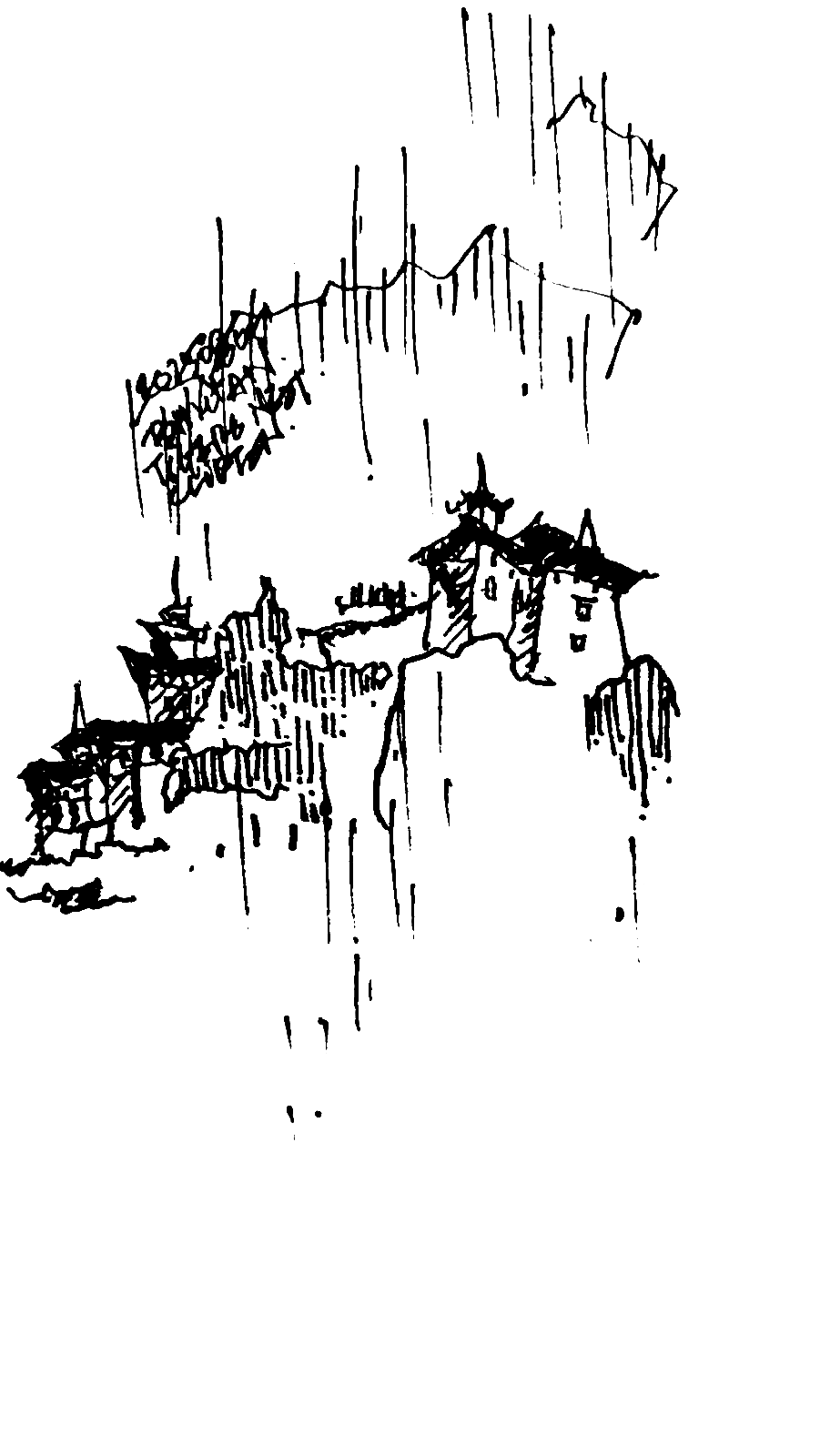

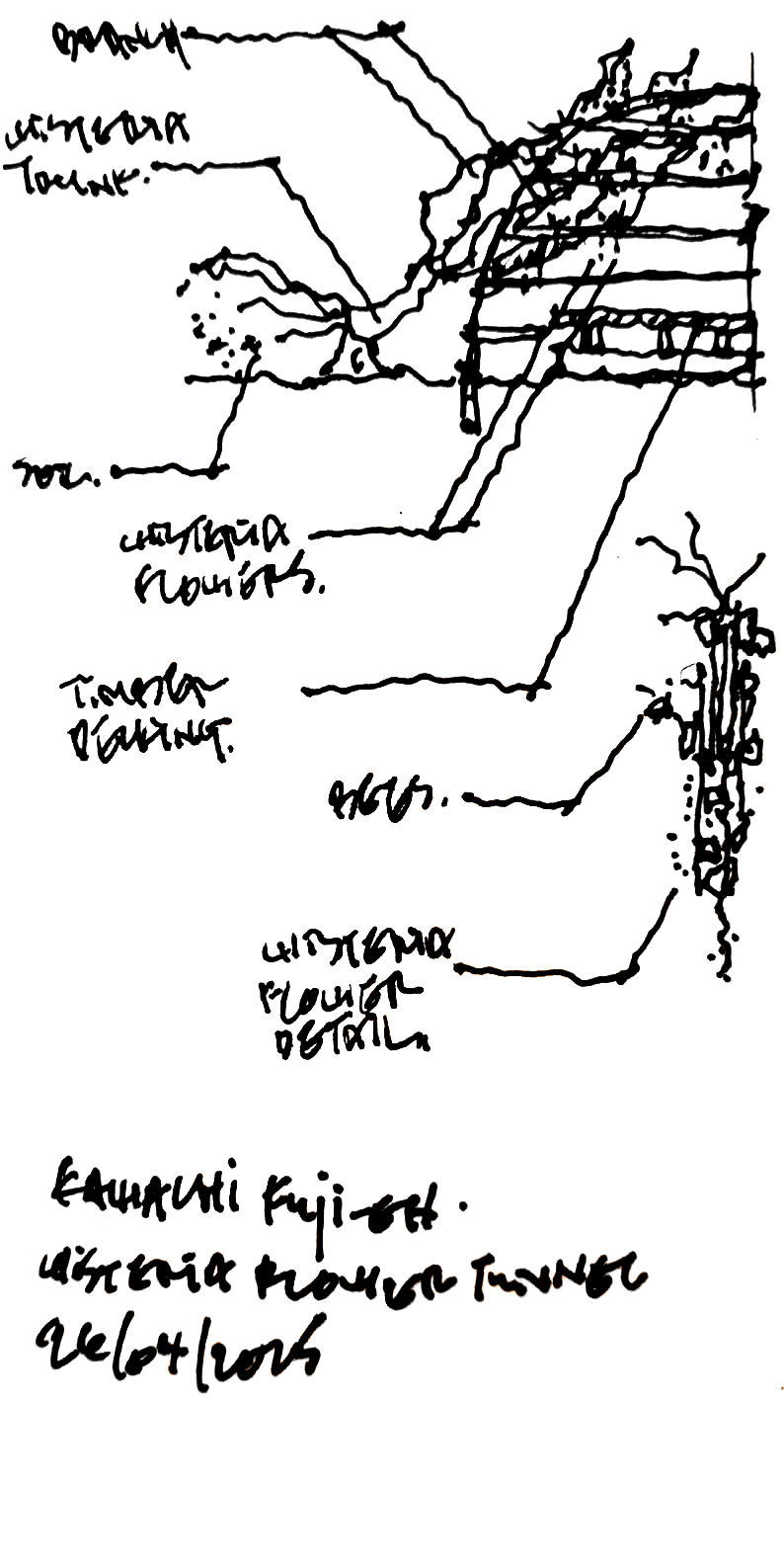

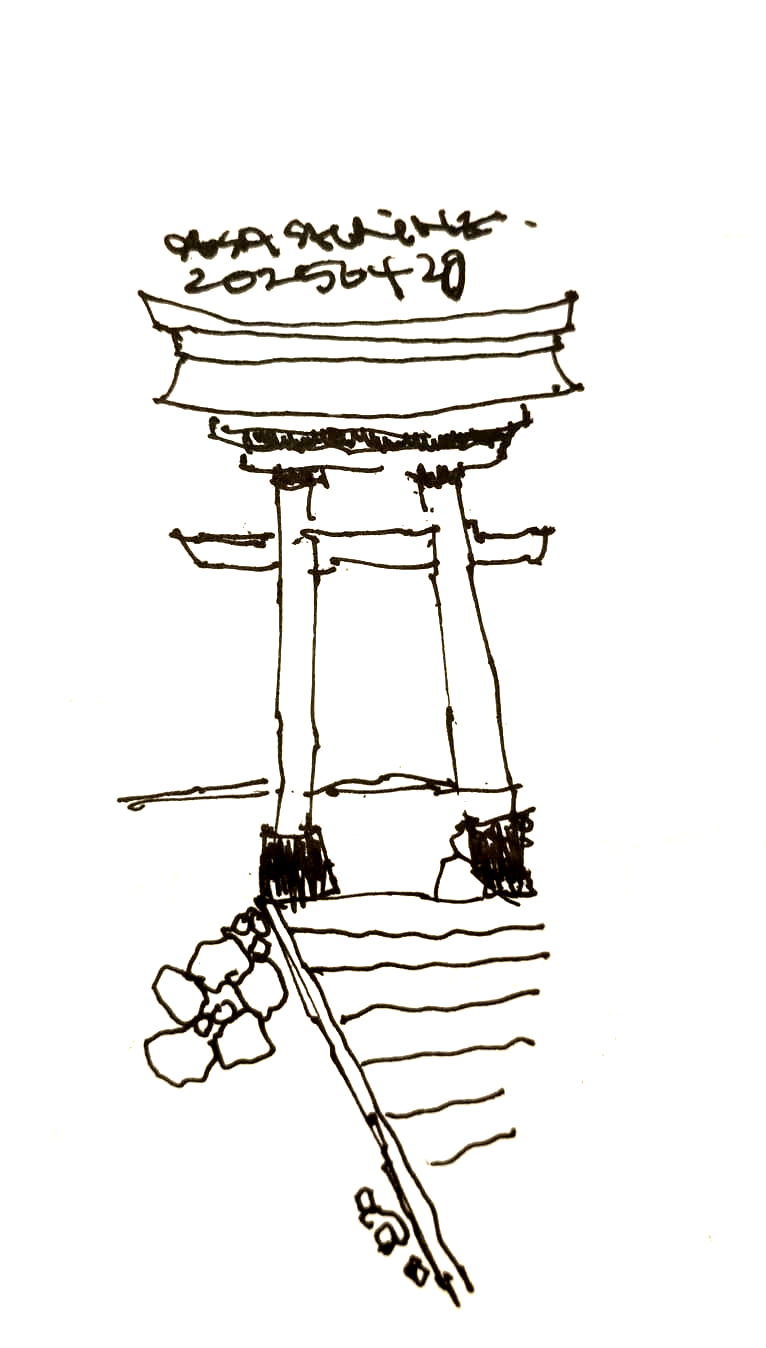

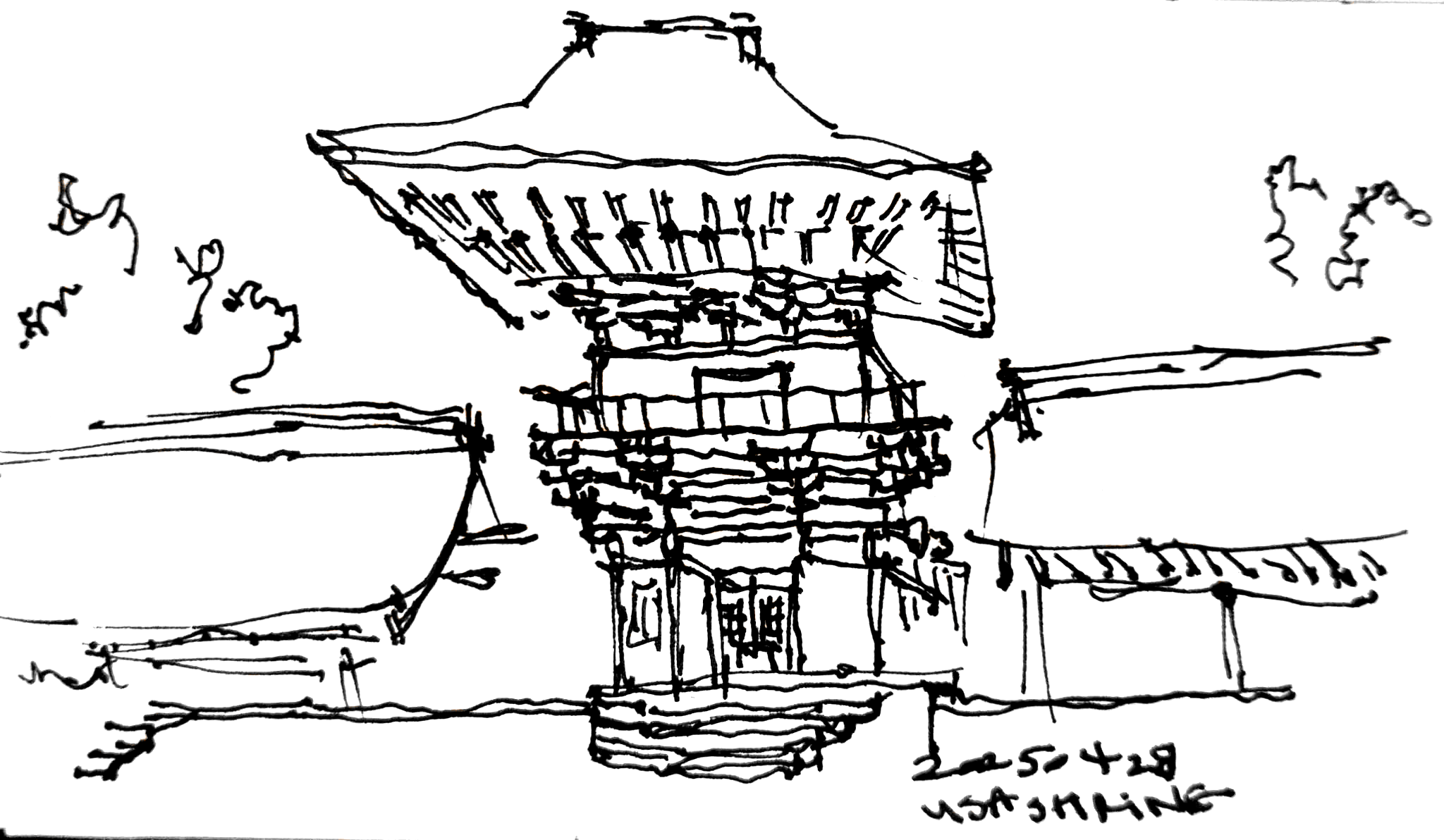

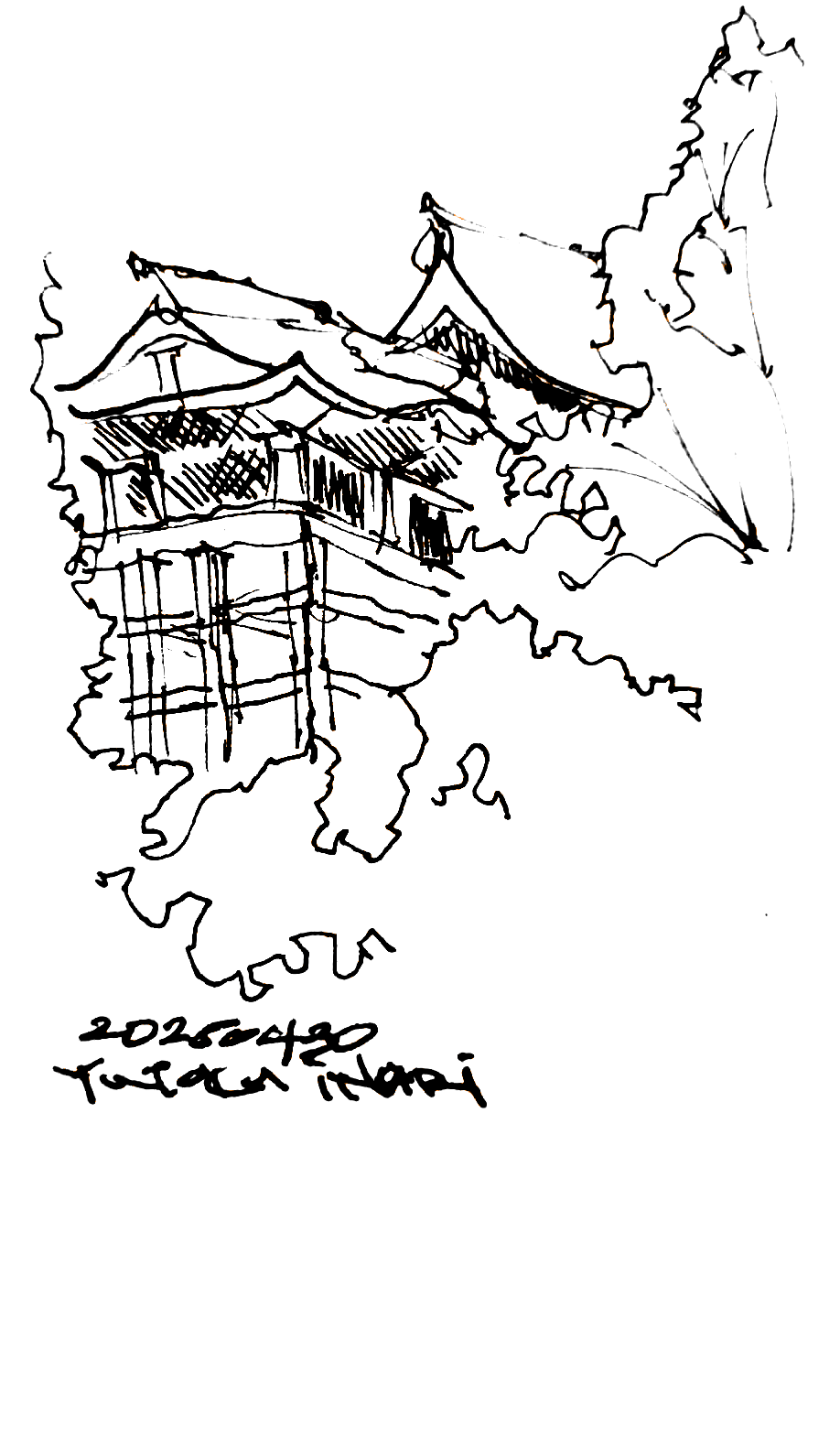

Japan 2025 SketchesA collection of sketches in Japan (Kyushu), Year 2025.Medium used: TWSBI Diamond 580AL ('F' nib) loaded with carbon black pigmented ink.

Japan 2025 SketchesA collection of sketches in Japan (Kyushu), Year 2025.Medium used: TWSBI Diamond 580AL ('F' nib) loaded with carbon black pigmented ink.

Manai no Taki, Takachiho, 27 Apr 2025

Kawachi Fuji-en, Kitakyushu,

26 Apr 2025

Manai no Taki, Takachiho,

27 Apr 2025

Tori Gate of Usa Shrine, Usa,

28 Apr 2025

Usa Shrine, Usa, 28 Apr 2025

Yutoku Inari Shrine, Kashima Saga, 30 Apr 2025

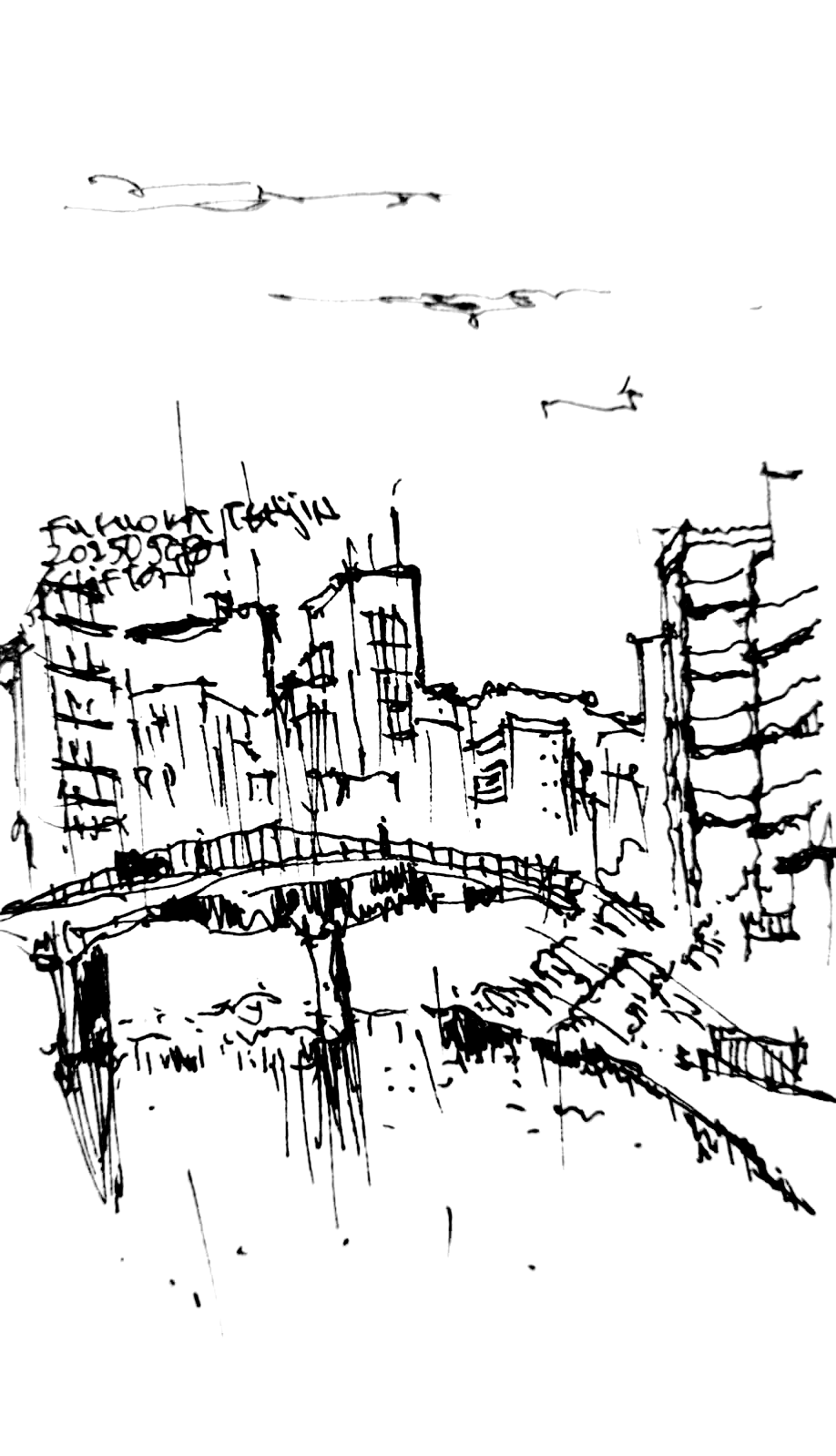

Tenjin, Fukuoka, 08 May 2025  Japan 2024 SketchesA collection of sketches in Japan (Kanazawa & Toyama), Year 2024.Medium used: TWSBI Diamond 580AL ('M' nib) loaded with carbon black pigmented ink.

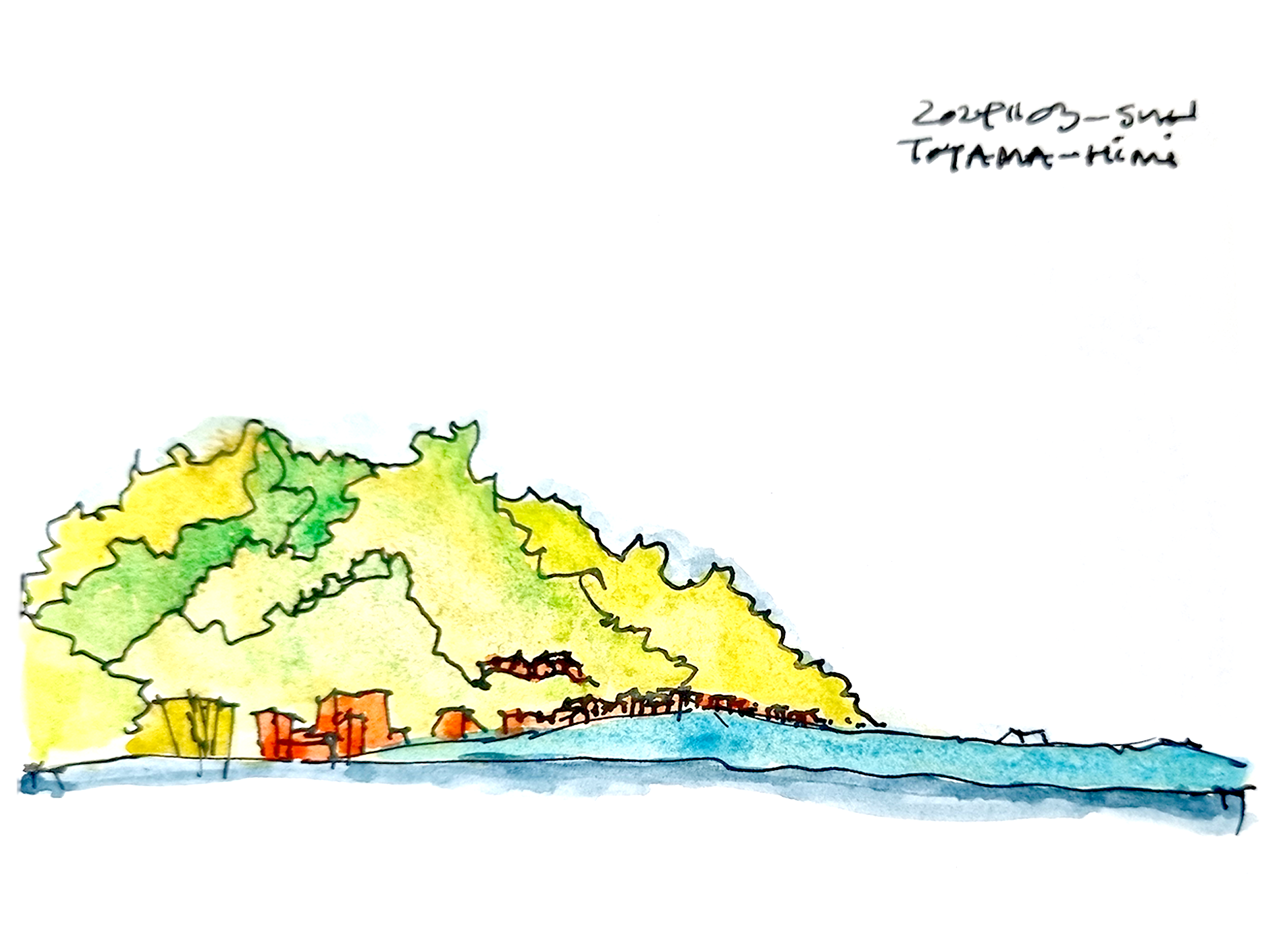

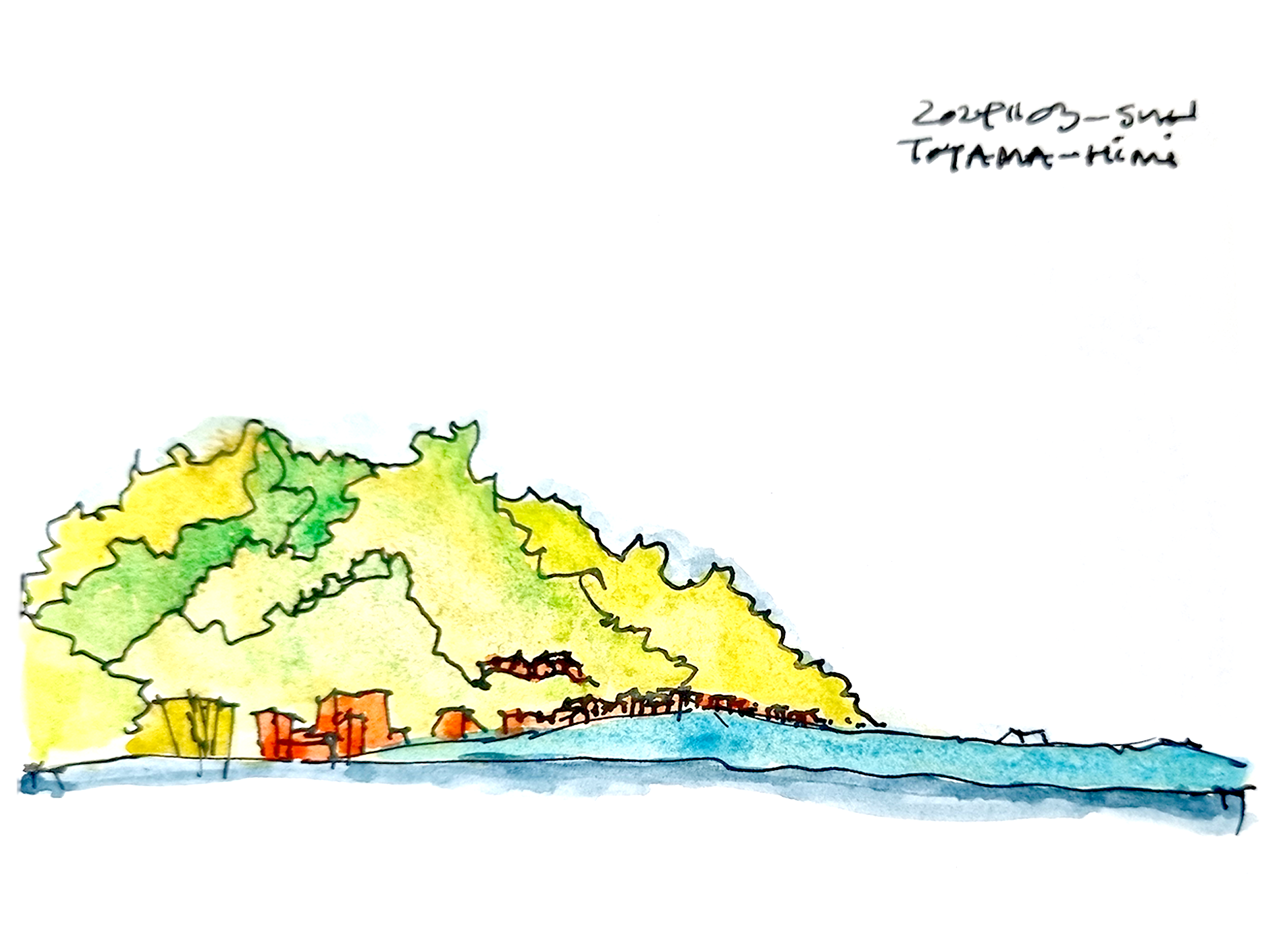

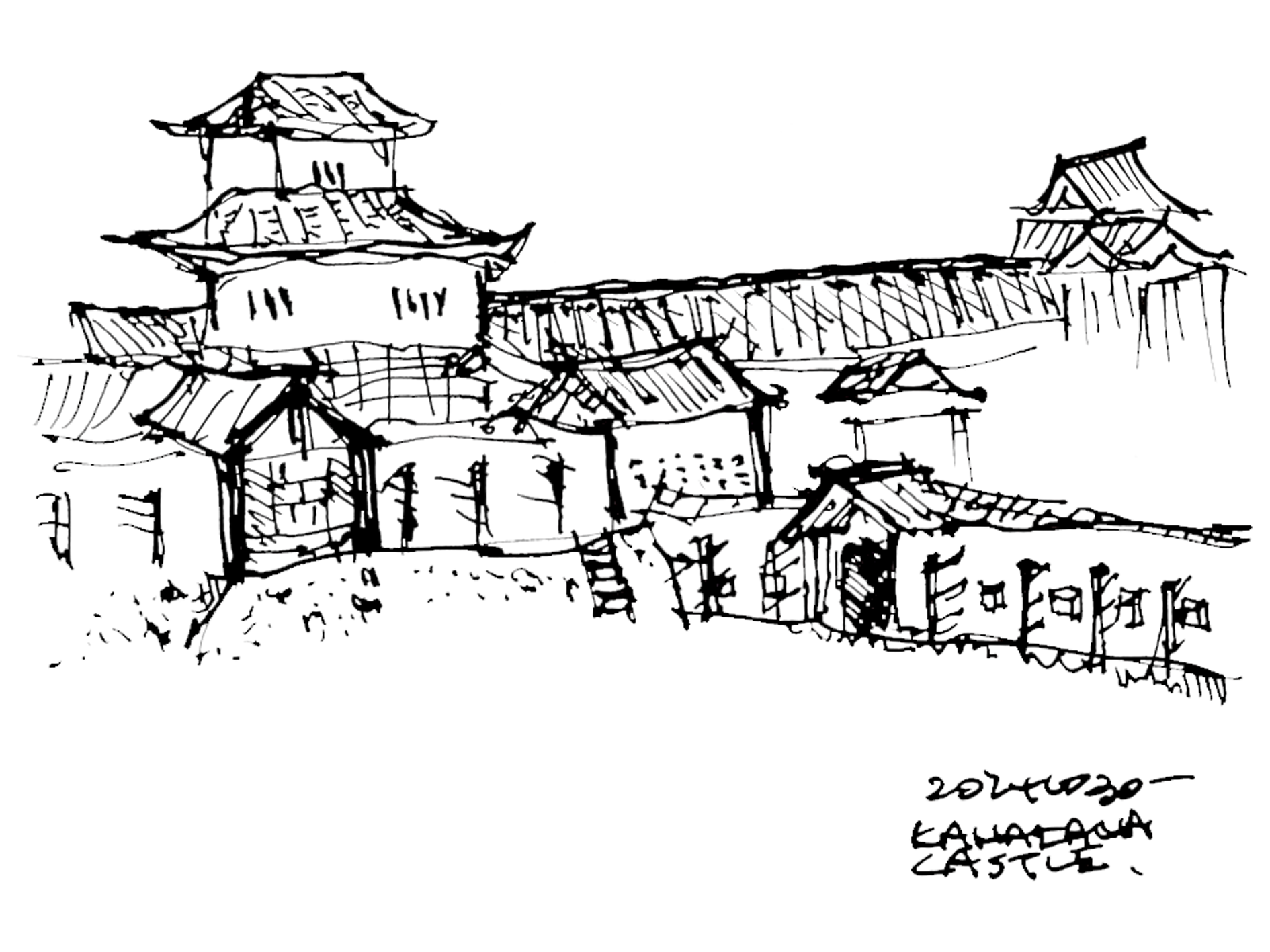

Japan 2024 SketchesA collection of sketches in Japan (Kanazawa & Toyama), Year 2024.Medium used: TWSBI Diamond 580AL ('M' nib) loaded with carbon black pigmented ink.

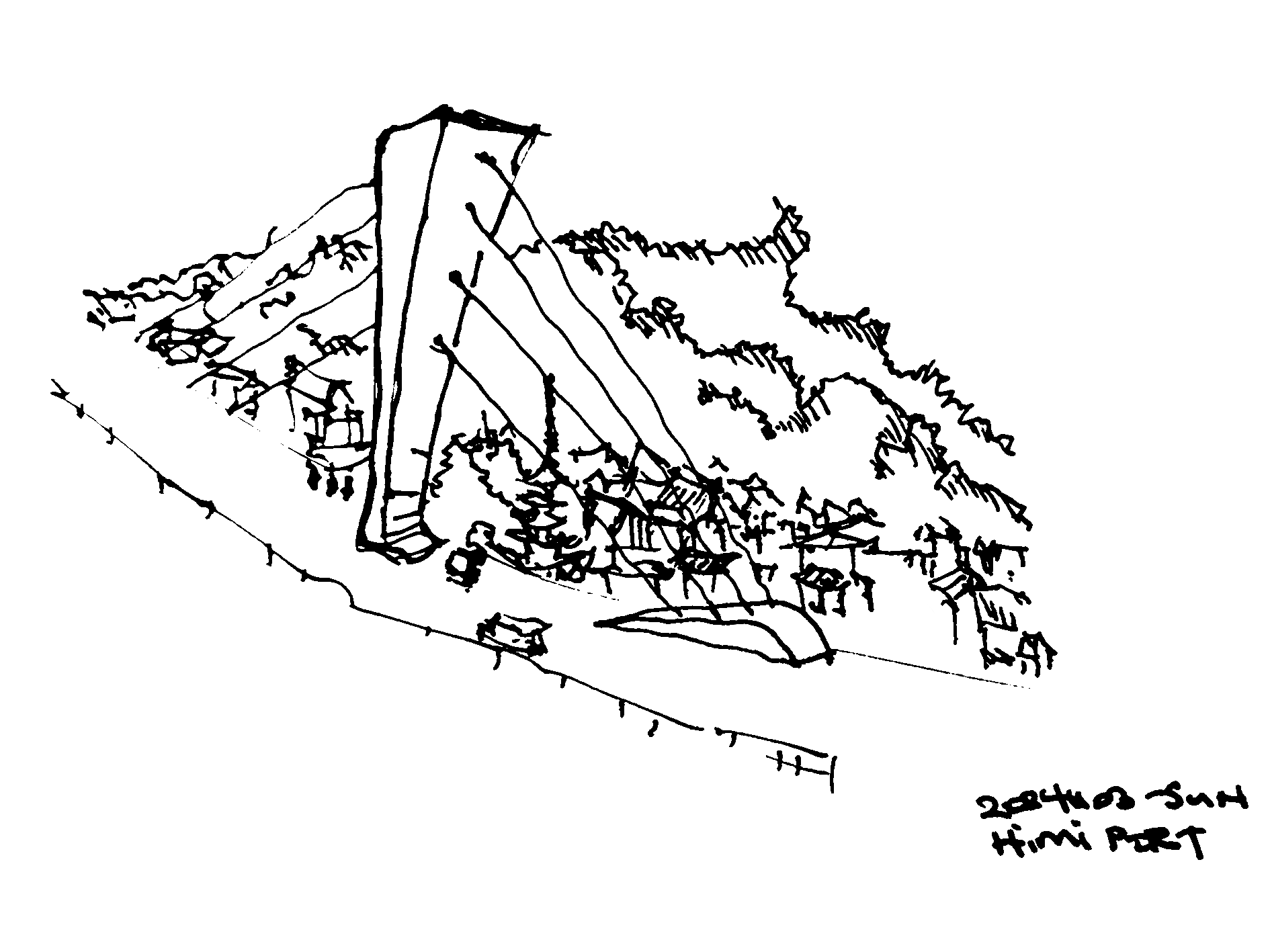

Himi Port, Toyama, 03 Nov 2024

Kanazawa Castle, Kanazawa, 30 Oct 2024

DT Suzuki Museum, Kanazawa, 30 Oct 2024

Himi Port Bridge, Toyama, 03 Nov 2024

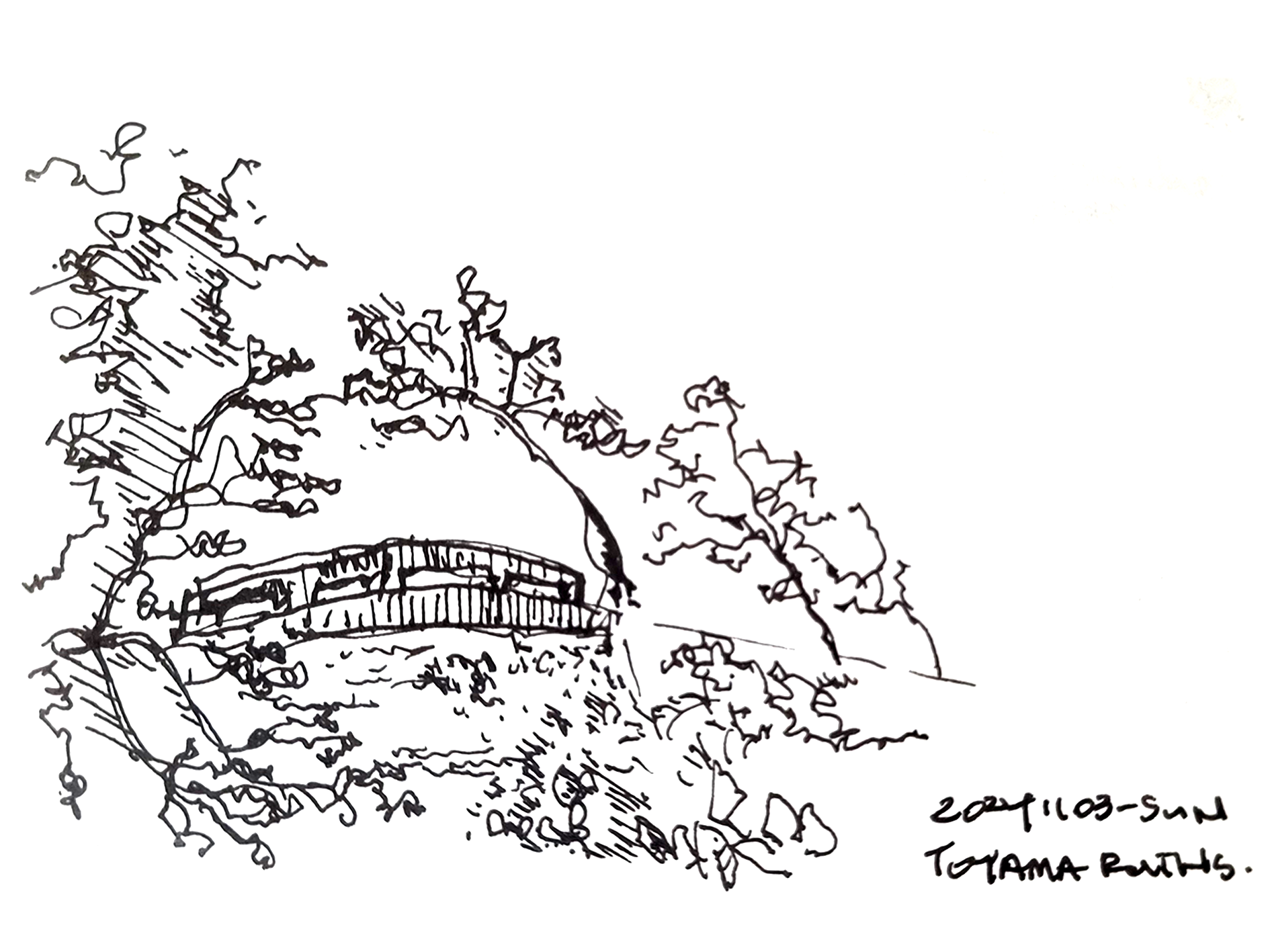

Takaoka Old Castle Park, Toyama, 03 Nov 2024

Kansui Park, Toyama, 04 Nov 2024

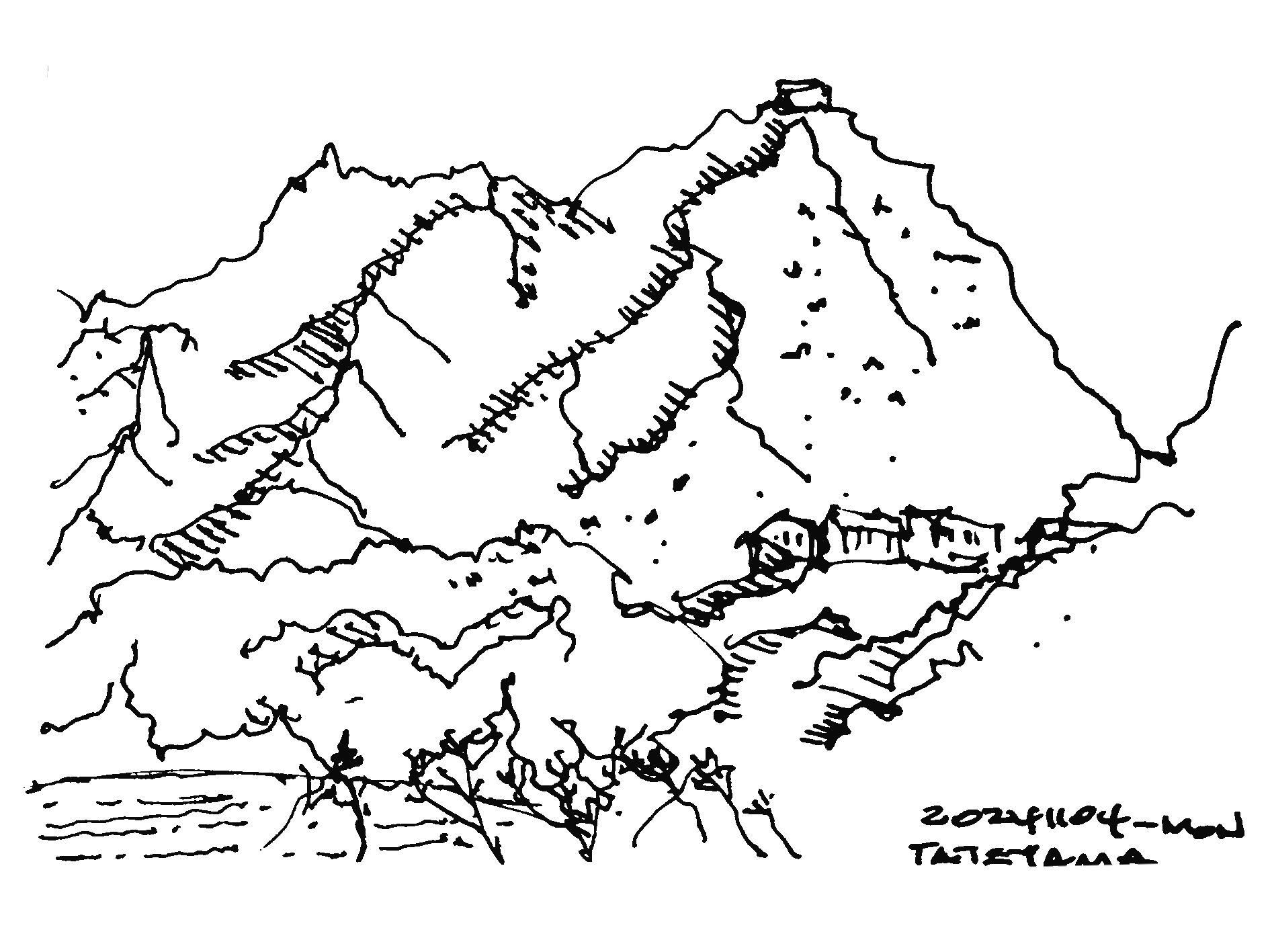

Tateyama Murodo, Toyama, 04 Nov 2024

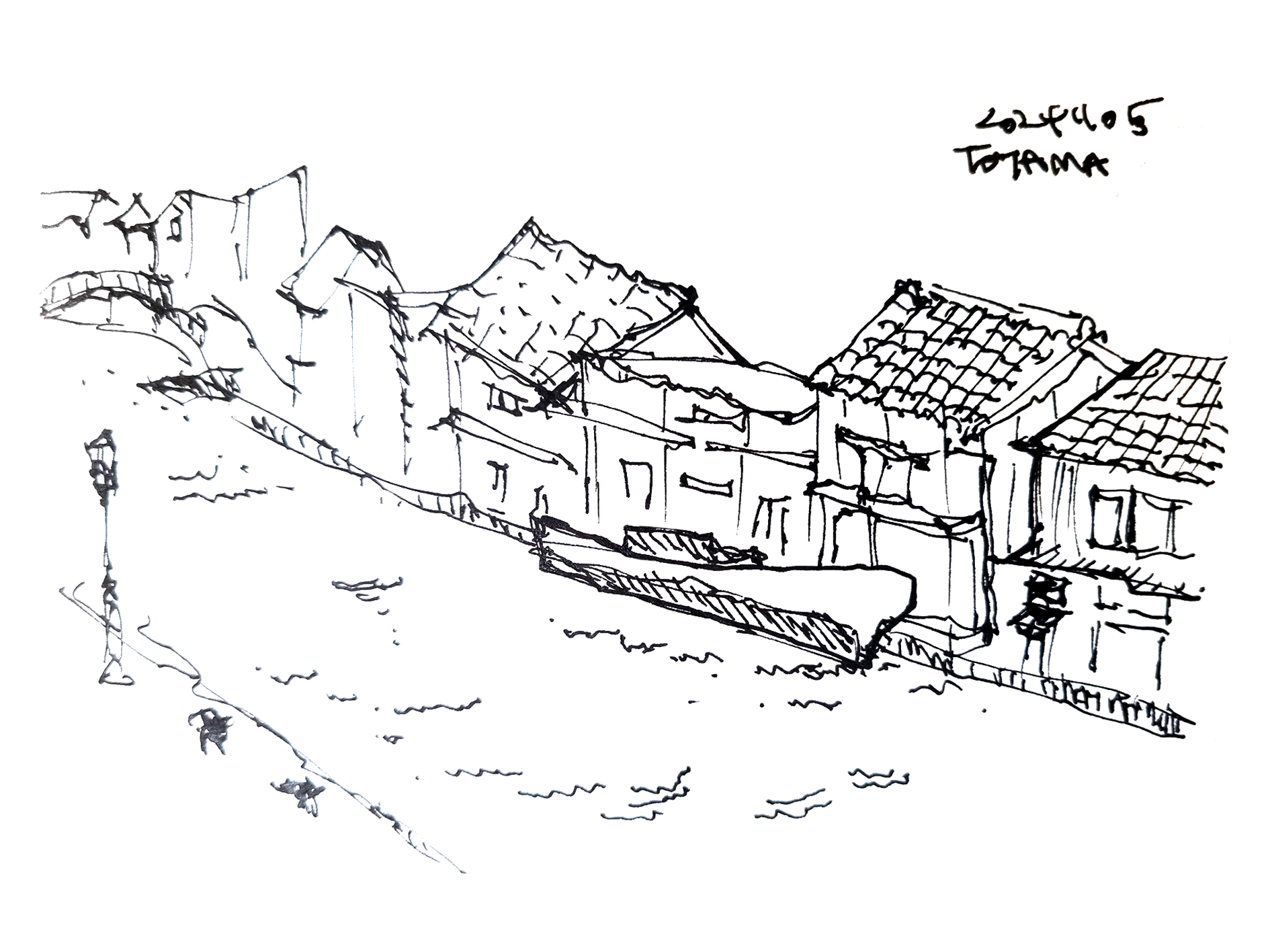

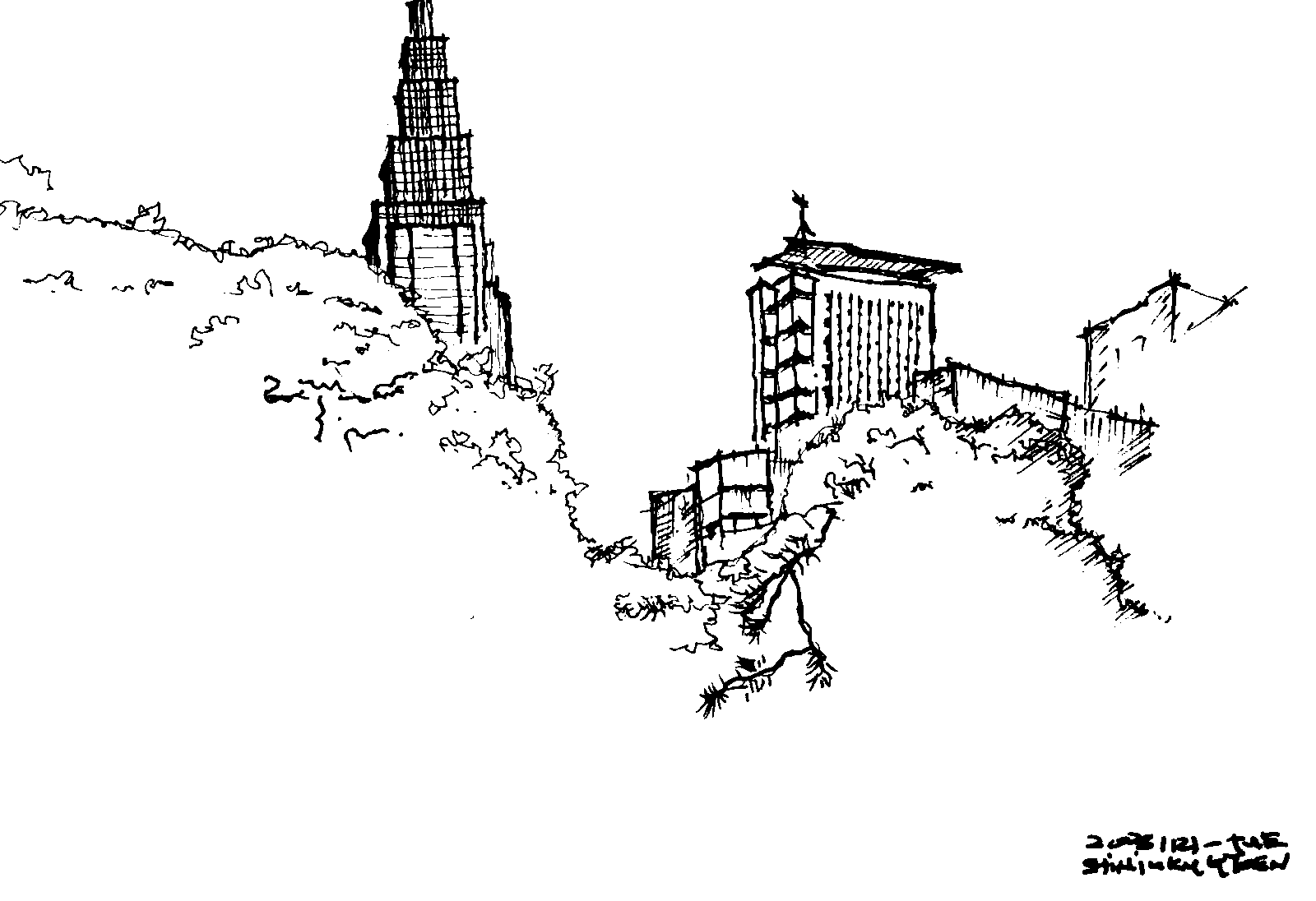

Kaiwomaru Park ("Little Venice"), Toyama, 05 Nov 2024  Japan 2023 SketchesA collection of sketches in Japan (Fuji, Kyoto, Tokyo, Takeyama), Year 2023.Medium used: TWSBI Vac 700R ('M' nib) loaded with carbon black pigmented ink.

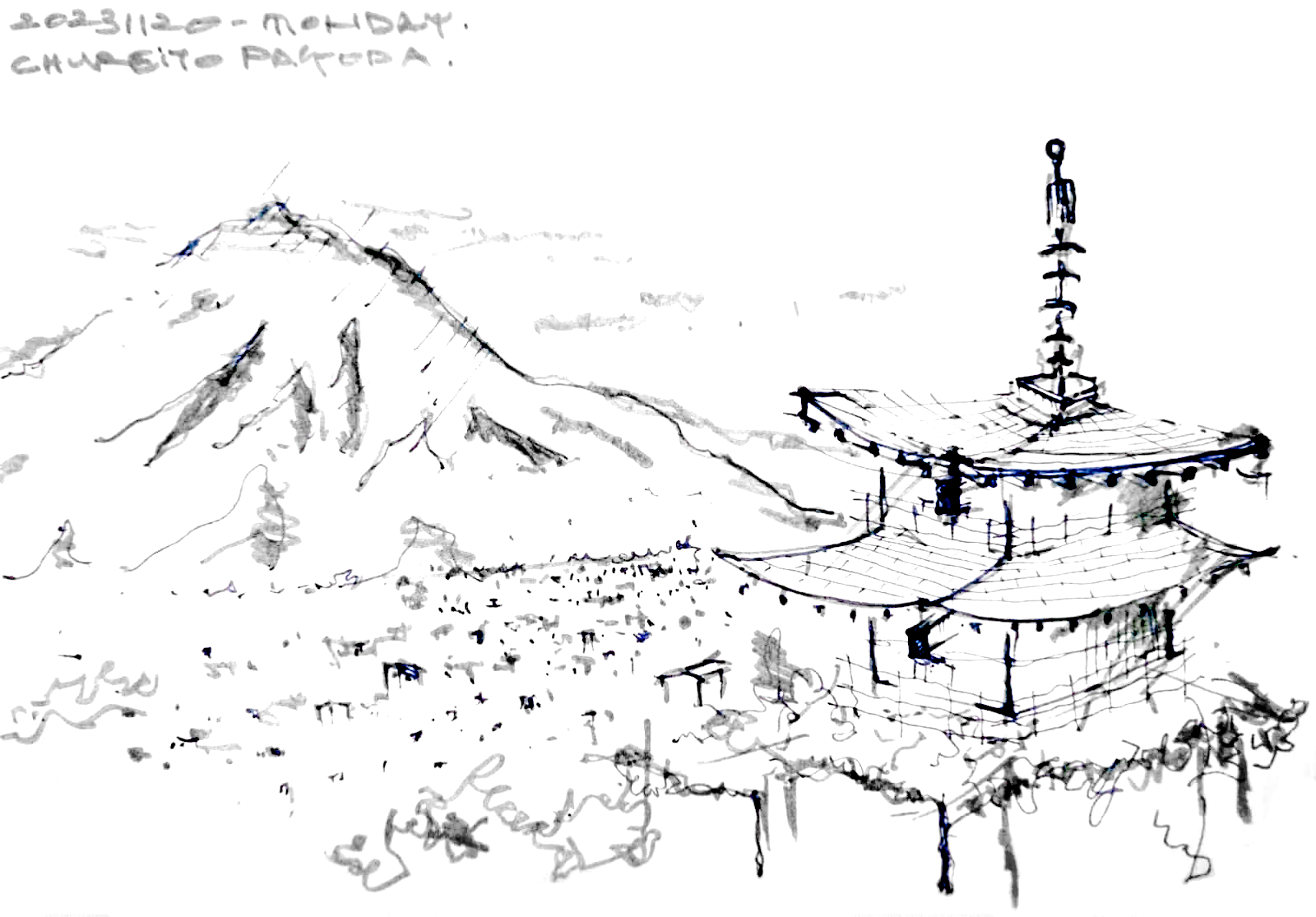

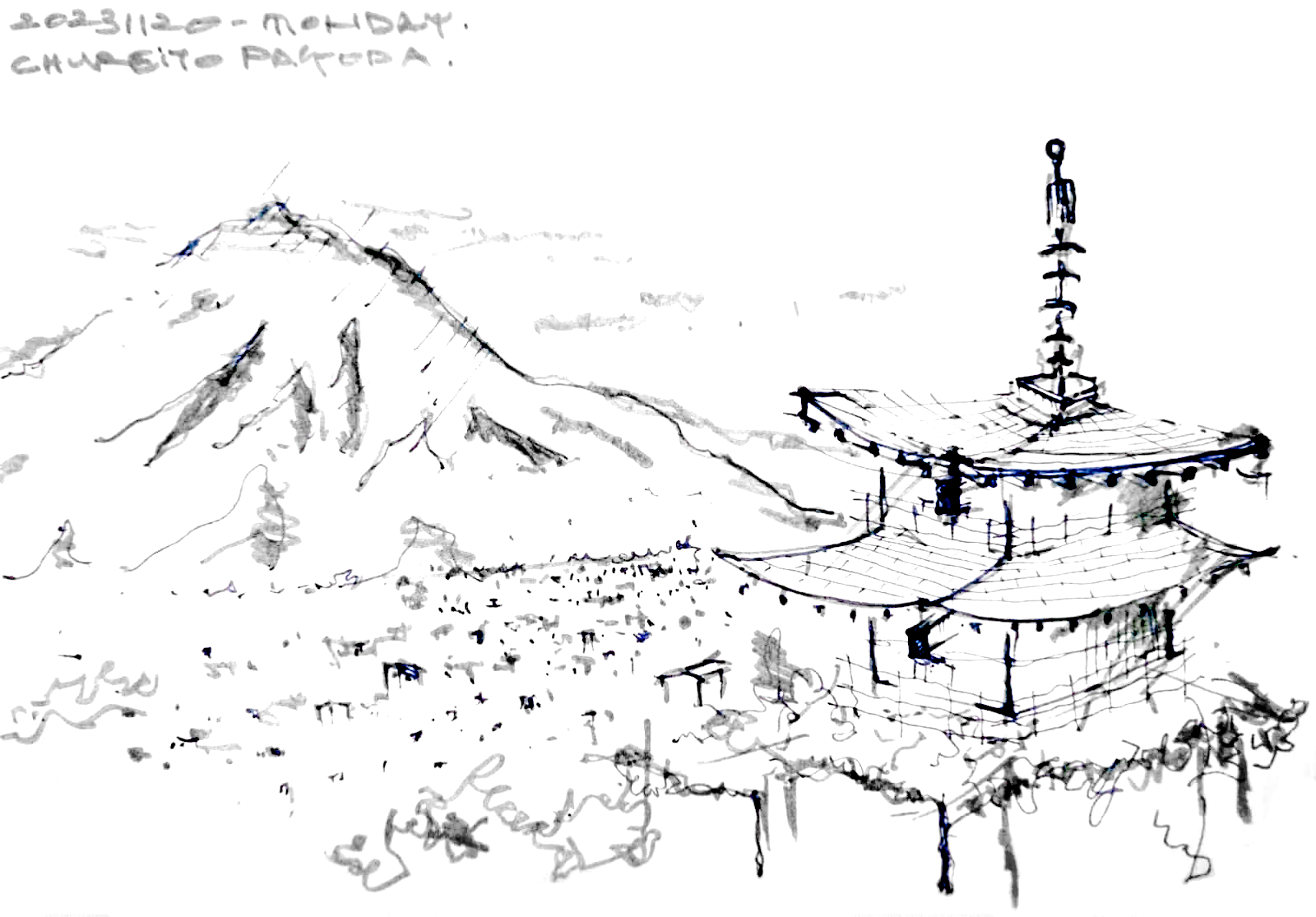

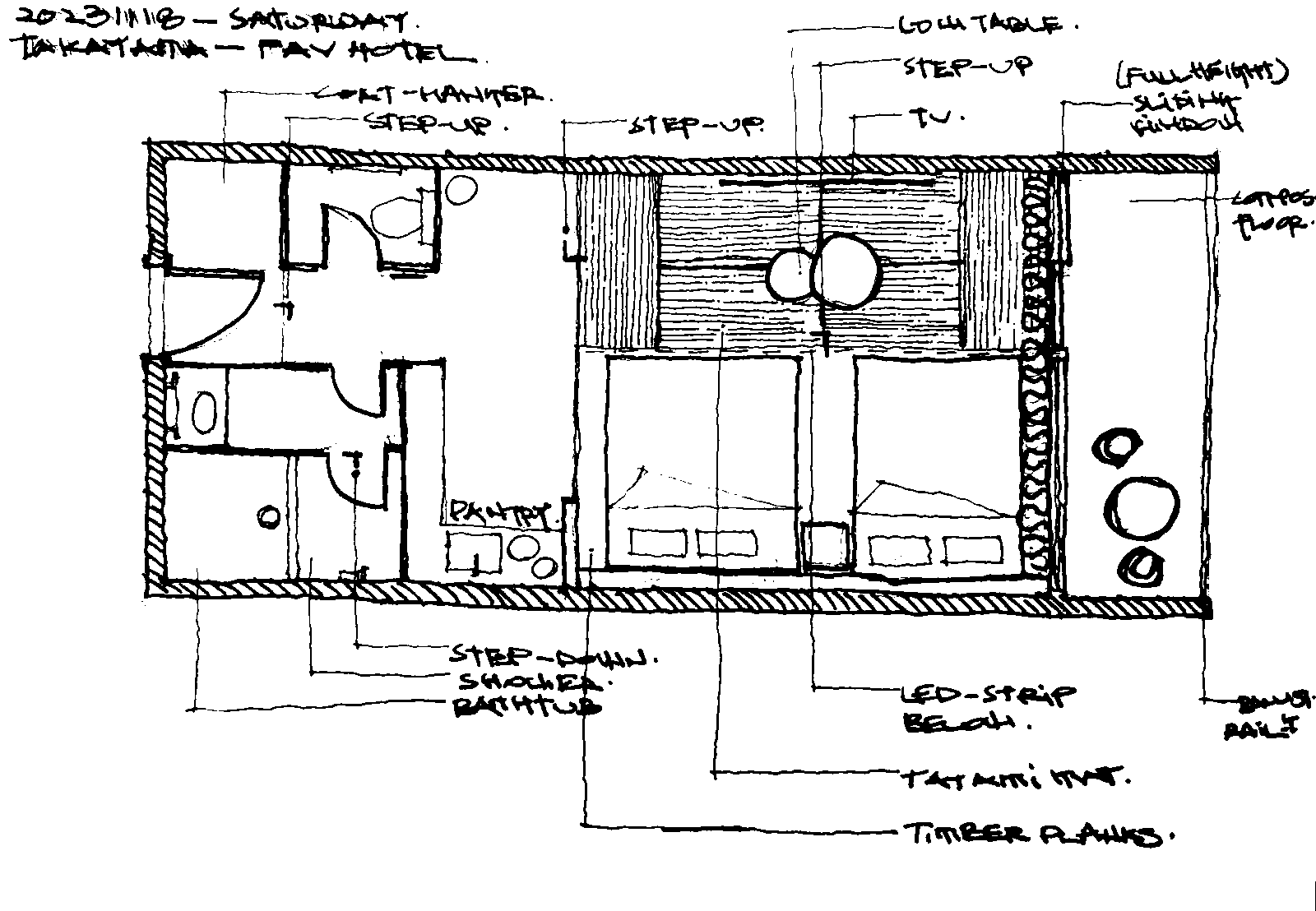

Japan 2023 SketchesA collection of sketches in Japan (Fuji, Kyoto, Tokyo, Takeyama), Year 2023.Medium used: TWSBI Vac 700R ('M' nib) loaded with carbon black pigmented ink.

Chureito Pagoda, Fujiyoshida, 20 Nov 2023

Fav Hotel, Takeyama, 09 Nov 2024

Hostel Inn Gion, Kyoto, 10 Nov 2023

Shinjuku Gyoen, Tokyo, 21 Nov 2023

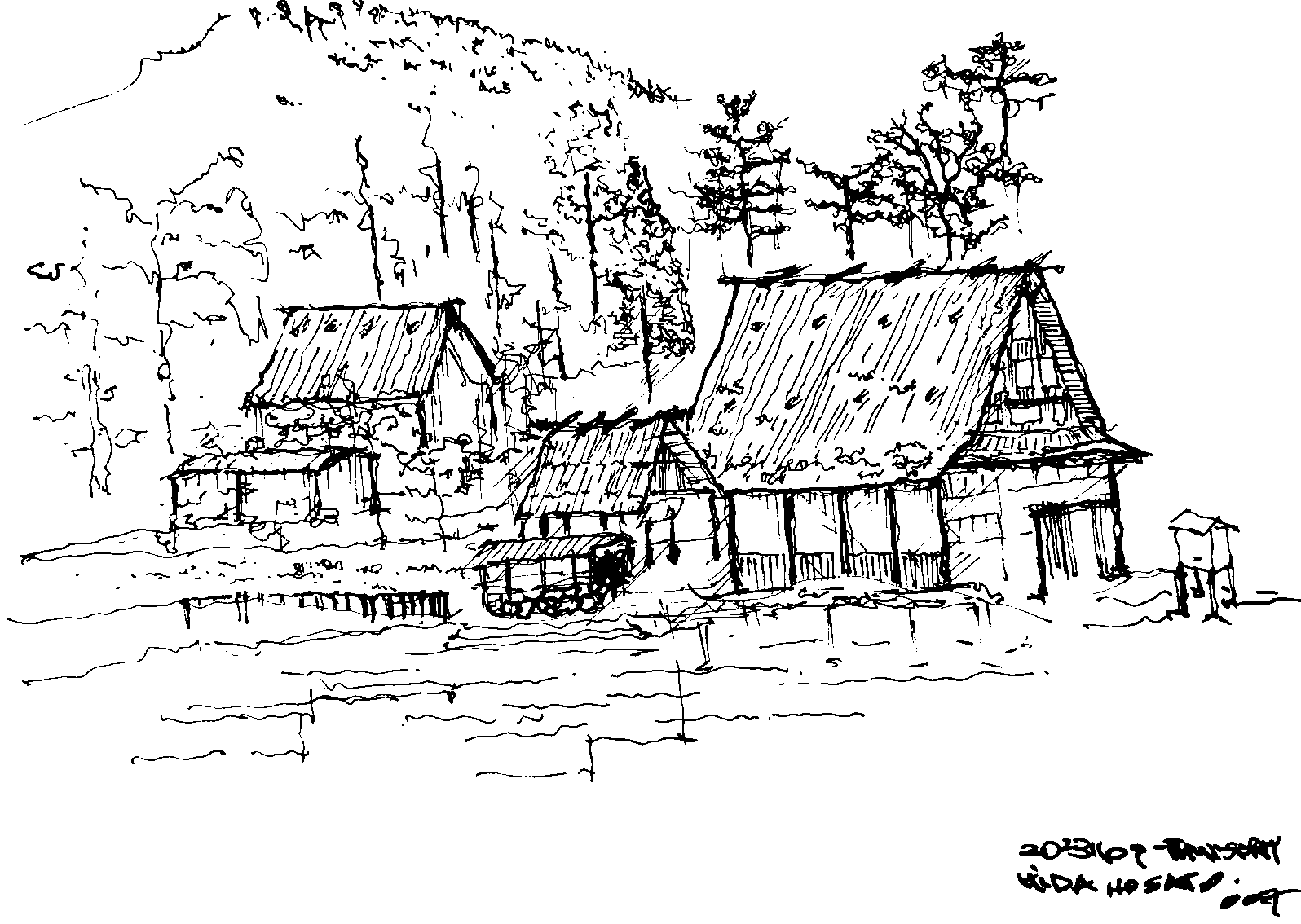

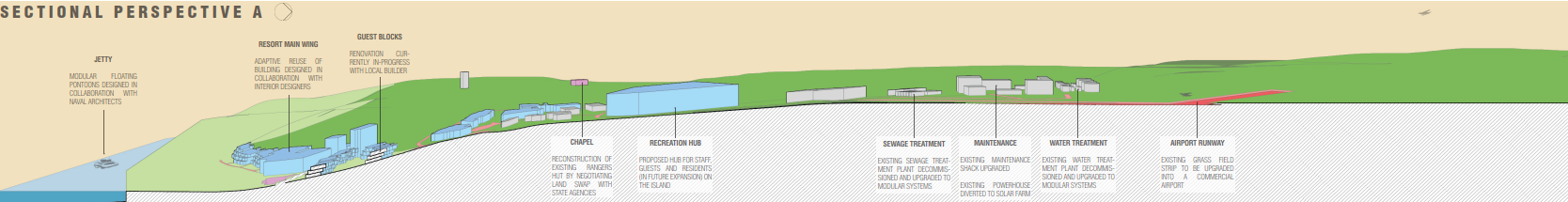

Hida no Sato, Takeyama, 09 Nov 2023  Lindeman Island Resort

Lindeman Island Resort

Project Description

Project DescriptionIsland Resort Re-Development comprising 14 blocks of 3-storey Hotel Guest Accommodation (210 units), 1 block of Public Facilities including Arrival Reception, F&B and Leisure spaces, and Infrastructure comprising of Jetty, Water & Sewage Treatment Plants, Solar Farm, and commissioning of 1 Catamaran boat.

Introduction

Tasked with redeveloping the abandoned island resort along the Great Barrier Reef in the Whitsundays, there were ample opportunities in the Design, Build and Operate phases. The original Lindeman Island Resort was abandoned in 2012 after Cyclone Yasi damaged the resort’s facilities. Fast-forward to 2023, the island was purchased by Well Smart Group, and my primary task as the in-house Project Architect-and-Manager was to spearhead this redevelopment project. Some of my responsibilities were to lead my planning consultants to achieve compliance with the state and agencies, re-planning of the island in-house, managing my Design and Technical consultants on the Infrastructure and Interior Design solutions, organising supply-chain logistics from factory to site (including plants and infrastructure) and collaborating with the local Builders and vendors on contracts and technical performance on-site, to realise the renovation of 210 rooms, among other milestones.

Design DriversEnvironmental factors drive the decision-making process for this project. From a Developer’s standpoint, sustainable design, construction and processes reduce maintenance costs in the long-run. It is a powerful incentive for businesses serious for the long-haul. As such, infrastructure plants and building materials were designed to be modular to increase construction efficiency, to be resilient against cyclones and to provide the flexibility for future expansions when necessary. The upgraded island will boast of an ‘off-the-grid’ power supply, along with a water dam expansion and modular water treatment plants to sustain the entire island’s basic needs, without intervention from the mainland.

Adaptive ReuseApart from Environmental factors, another main consideration was to retain as much structures as possible to keep construction costs low. Partnering with one of the top Design Firms in Australia for the Master Plan and Interior Design of the Main Building and Guest Rooms, this limitation is viewed as a opportunity to re-purpose architecture design with more sensibility and sensitivity without removing the existing value and engineering on the island.

Project, Construction & Supply-Chain ManagementMaterials are sourced directly from overseas factories to ensure a strict quality of Furnitures, Fixtures and Equipment and are then planned strategically to be shipped to the island to meet time-efficiency and cost-efficiency.

From there, the Main Contractor Partner receives the materials and begins construction, with the Lead Project Architect (myself) ensuring that milestones are achieved in time and within budget, while resolving technical challenges on-site with the Contractor and Consultants.

JettyPartnering with another Singapore-based supplier for its proprietary modular pontoons, the new jetty is designed with 20 floating pontoons and a minimal number of piles (below 4 concrete piles into the seabed during design phase) to minimise damage to the seabed, reducing the negative environmental impact to the Great Barrier Reef. This Proprietary technology and design of the floating pontoons also facilitate efficient transport and assembly of said modules directly on the open waters.

InfrastructureSolar cells and batteries, water treatment and sewage treatment plants are designed for modularity and shipped over to the island for quick ‘plug-and-play’ installation.

Airport & RunwayThough at its initial phase, plans for an airport and a runway had led to literature research, preliminary design brainstorming, operational process considerations and soft vendor negotiations.

Partners and technical specifics have been redacted due to confidentiality policies. Mantra Club Croc Airlie Beach

Mantra Club Croc Airlie Beach Project Description

Project DescriptionHotel Resort Renovation comprising 5 blocks of 3-storey Hotel Guest Accommodation (160 units). Project management of renovation process while hotel was still in operation.

IntroductionA popular domestic tourist destination, Mantra Club Croc at Airlie Beach had undergone another cycle of renovations, focusing on the Guest Room design to provide a fresh and bright aesthetic for guests. The project was facing major delays and material shortage and I was brought on to push the project of 160 rooms to completion.

Challenges: Varying Room TypesOne prominent challenge faced during this project was the number of room types in this hotel. Due to it’s unique existing design, every block has a unique layout which complicated the design and logistics of the project. The process required strict and accurate documentation of the design and dimensions of Furnitures and Fixtures, to be communicated to the factories for precision manufacturing.

Challenges: Unfavourable LogisticsPrior to my insertion, the materials on-site were poorly inventorised and stored, leading to damaged materials during the cyclone season in Australia or missing inventory. To grit through the project, stricter processes and protocols were established to ascertain the actual inventory of materials. New materials had to be ordered from the factories and arranged to be shipped as per the new Project Program, while the builders concurrently started on the renovation.

Due to the international nature of the value-chain, the timeline to complete works became tighter. The Project Program had to take into account manufacturing and shipping lead time, labour downtime (both from overseas factories and local vendors), and varying seasons, especially when Australia was situated in the southern hemisphere.

Challenges: Concurrent Hotel OperationsRepresenting the owner of the property, the prime directive was to minimise monetary loss for the owner by concurrently running the hotel operations together with the renovations.

Detailed planning and close coordination with the Hotel Management Team were paramount to the success of the project as we had to consider aspects of hospitality and construction management and find a common ground to operate concurrently.

Photo Credits: Well Smart Group, Mantra Club Croc with Accor Group and Steve Scalone

Photo Credits: Well Smart Group, Mantra Club Croc with Accor Group and Steve Scalone Queen's Arc (HDB)

Queen's Arc (HDB) Project Description

Project DescriptionPublic Housing Development comprising 1 block of 23/32-storey & 1 block of 29/39-storey Residential flats (610 units), 1 block of 25-storey Rental flats (234 units), Commercial & Social Communal facilities, 1 block of 6/6-storey Multi-storey Carpark with Roof Garden, 2 Precinct Pavillions and ESS.

IntroductionThe project was a public housing development by the Housing Development Board (HDB). After completing the project in Yishun, the project team was assigned to this project located in Queensway. As part of my continuing duties as a Project Architect for the Main Contractor, I was heavily involved in technical coordination and sub-contractor onboarding to kickstart the project. My peripheral duties included clinching the Green Mark Gold and to manage the health of a retained tree within the construction site.

Challenges: Noise ControlSituated next to Alexandra Hospital, a key operational requirement was to maintain the construction noise to a lower than normal decibel point. This requirement was vital to ensure that patients receiving care at the hospital would not be affected by the construction noise. This was especially challenging during the piling phase, where the piling rigs were constantly operating. Usually, the Main Contractor would prefer to speed up the piling process by increasing the number of active piling rigs. This allows for better cashflow as the claims for such works are substantial. Futhermore, the piling process is a long but an essential task within the Critical Path. Including all required inspections on-site, Cube Tests, curing of concrete and Ultimate Load Tests, this process may span from 6 months to a year, largely depending on the multiple variables.

Sensors were installed at different points on-site to capture real-time acoustics data on-site. This data is then transmitted to the hospital for their monitoring. In order to reduce the noise levels of construction, the project had to make informed and strategic trade-offs. One of which was the project timeline, as fewer piling rigs were active on-site, thus reducing the noise levels at any given time, but also lengthening the duration of the project.

Challenges: Underground Works CoordinationUnderground services require advanced planning and coordination among all disciplines. Though hidden away from the residents, these services are critical to the proper and seamless functioning of the entire development. Mistakes within the coordination process can lead to major abortive works, financially burdening the builders and eating into their profits. Some services generally observed in any project include electrical and internet lines, plumbing pipes, house drains and major drains leaing to the central catchment, and structural piles.

This project also had to accommodate a Pneumatic Waste Conveyance System (PWCS) and the infrastructure for the Active, Beautiful, Clean (ABC) Waters Programme. The PWSC network utilises vacuum technology to automate the waste disposal process. Waste is transported via large underground pipes to a central collection point. The PWCS is regulated by the National Environment Agency (NEA). The ABC Waters, initited by the Public Utilities Board (PUB), serve as a temporary water catchment area for the development. Not only does the collected water beautify the landscapes within the estate, it also serves to irrigate nearby flora and is an essential element to encourage growth of biodiversity.

Due to the large sizes of PWCS pipes and the additional drain and irrigation network required for the ABC Waters, the underground services coordination became more complex, requiring more detailed clash studies and further technical coordinations with all relevant stakeholders.

The ABC Waters was also designed to be integrated with the Detention Tanks underground, and an additional water security measure. As such, more stringent requirements were set by PUB, and experts were brought on-board to ensure that these special functions were operational.

Contributions: Green Mark (Gold)Though it was unusual for the builder to lea the Green Mark application process, the contractual obligation eventually fell on my lap. The team brought on Green Mark consultants to guide us through the process, while I stepped up to lead the consultants. Instead of passing all responsibilities off to the Green Mark team, I was heavily involved in the entire process, serving as a technical bridge between technical personnels (TP), such as the consultant TPs, the builder’s project team and the Green Mark team.

To ensure accurate and efficient flow of information, I personally calculated the Concrete Usage Index (CUI) of precast and cast in-situ concrete and architectural materials. I had designed a unique process which utilises databases and computational formulas to automate this process. With this, the CUI of future projects can be calculated more efficiently by inputting raw data unique to the project into the database. This CUI automation assisted the consultants tremendously in their work processes, building up to successfully clinching the Green Mark Gold for the project.

Contributions: Management of Tree Health

Due to an order from NEA to retain a specific tree on-site, this responsibility also fell upon me to manage the health of the tree, which can (and was) affected by the on-going construction. Working together with arborists, the landscape architect and landscape specialists, the health of the tree was properly managed.

The root cause of the initial deterioration of the tree was due to the water runoff and site boundary design. The tree was located on a steep slope. At the end of the slope was the site boundary, where the perimeter was casted in concrete to erect hoarding boards. Due to the surrounding construction, the tree was already physically stressed with the harsh environment which lacked nutrients. The water collected at the foot of the slope where the concrete footing was casted added to the physical stress. The led to the roots of the tree taking in a lot more water than required.

After consulting with the arborist, two temporary solutions were executed. First, permission was given to prune the tree. This would reduce the minimum nutrients needed to sustain the tree. Second, water was consistently pumped out of the pit. During my tenure, I had studied a permanent solution to drain off excess water and plans were underway to inlay pipes, using a combination of gravity and mechanical pumps to assist the draining of the excess water.

While the project completed substructure works, I was urgently head-hunted to crisis-manage an on-going project for a developer and kickstart another island development. The developer had weighed the cost-benefits and decided to buy me out to reduce their losses on the on-going project, while setting up strong foundations for the island development, which would lead to future additional profits. It was with a heavy heart that I took up their urgent offer and left the project team.

While the project completed substructure works, I was urgently head-hunted to crisis-manage an on-going project for a developer and kickstart another island development. The developer had weighed the cost-benefits and decided to buy me out to reduce their losses on the on-going project, while setting up strong foundations for the island development, which would lead to future additional profits. It was with a heavy heart that I took up their urgent offer and left the project team. Forest Spring (HDB)

Forest Spring (HDB) Project Description

Project DescriptionPublic Housing Development comprising 8 Blocks of 13-storey Residential flats (756 units), including Commercial & Social Communal Facilities, single-storey Carpark, Precinct Pavillion and ESS.

IntroductionLocated along Yishun Avenue 1, this public housing development by the Housing Development Board (HDB) of Singapore was my first project fresh out of Architecture school. Contrary to the usual pathway of a fresh Architecture graduate, I took on this development as a builder’s Project Architect. Hired by the Main Contractor who was awarded this construction project, my scope was two-fold: (i) to manage the Architectural built-quality and progress, and (ii) to resolve technical building issues on-site. In essence, I served as a bridge between the current Architectural Manager and Architectural Coordinator, taking on a leadership and technical role. During my tenure, I helmed the liaison with government agencies with respect to statutory building requirements and submissions, and assisted with on-site supervision and documentation.

Under the company’s management, and project team’s leadership, this project earned notable awards: (i) Construction Award by Housing Development Board (HDB), (ii) CONQUAS1 Star by Building & Construction Authority (BCA), and (iii) WSH2 Council’s Safety and Health Award Recognition by BCA.

Forest Spring was also featured in local media The Straits Times in 2023 as a example of excellent built-quality amidst COVID-19 stumbles. Read the article here.

Challenges: Balance of WorksFrom the start, the project had roadblocks which were not favourable to the overall construction progress. Two major issues arose from this project being a Balance of Works contract.

Firstly, the overall construction timeline was shortened. The project team had to work with a 6-months handicap upon receiving permission to enter the site and take-over works from the original builder.

Secondly, an intensive site investigation had to be conducted to ascertain the works conducted by the original builder. This primarily focused on the exact piling locations, as well as technical coordination, such as the Combined Services Drawings.

Challenges: COVID-19 PandemicThe project struggled at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic which greatly affected building productivity.

Manpower Shortage

Due to enhanced restrictions following the COVID-19 outbreak, the entire workforce on site had to be zoned and segregated to minimise cross-clustering. This translated to reduced mobility and flexibility on-site. Workers could not freely cross their pre-approved zones, restricting operational strategies to ramp up productivity by allocating more workers to a specific block.

Furthermore, influx of new construction tradesmen was also cut by global labour restrictions. This meant that the maximum output within the industry was capped, with little possibility to ramp up output with fresh labour from overseas. Construction sites across Singapore were competing with the limited resources to push progress while maintaining a high built standard.

Apart from site constraints, all site personnel, including project personnel, were mandated to leave site once every two weeks for their “swab-test”, to ensure that personnels on-site were healthy and COVID-free. During the project timeline, a Stop Work order was issued due to an outbreak. This further impacted the project timeline.

Material Shortage

Similarly, with international trade restrictions, building materials were bottle-necked and unable to timely arrive into Singapore’s ports. The shortage of shipping containers added to the pressure, when Europe halted trading while manufacturers in China showed no sign of decelerating their production. This eventually resulted in a majority of empty containers stuck in Europe, while Asian manufacturers wait impatiently for any spare containers at their home ports.

Apart from advance and prophylatic project planning, intense negotiations, cooperation and out-of-the-box solutions had to be brainstormed and employed to meet the project milestones regardless of real issues faced on a global and nation scale.

Contributions: Automating Building ProductivityTaking charge of the Constructibility Score (C-Score), a mandatory score to be submitted to BCA, I automated the tracking of Building Productivity. This enabled quick comparisons of productivity across blocks to make decisive interventions on a bi-weekly basis.

This process also provided a systematic structure to approach and tackle site problems by visualising critical components and sub-processes of the entire construction value-chain.

The C-Score obtained for this project was 71.

Contributions: Handing-over ProcessThe Handing-over Process can be chaotic and tedious if the approach is disorganised, especially with multiple inspections from various stakeholders queued up. From ensuring that works are completed and ready for official inspections, to preparation of relevant documentations, to actual site-inspections and capping off with rectification works, this complex process requires a technical, disciplined and structured approach to seeing it through.

Eventually, all 756 dwelling units were sucessfully handed-over back to the developer within 2 months amidst constraints exacerbated by COVID-19, and Temporary Occupation Permits (TOP) for the development were issued earlier than originally planned.

Key project team members involved include Ting Huat Hwee (Project Manager), Thet Win (Architectural Manager), Ted Requelman (Archi Coordinator), Guo Jun (Project Engineer) and Francis Wong (M&E Coordinator), of whom I am immensely grateful for their guidance, teaching and leadership.

Key project team members involved include Ting Huat Hwee (Project Manager), Thet Win (Architectural Manager), Ted Requelman (Archi Coordinator), Guo Jun (Project Engineer) and Francis Wong (M&E Coordinator), of whom I am immensely grateful for their guidance, teaching and leadership. Optimal Concert Hall

Optimal Concert Hall Introduction

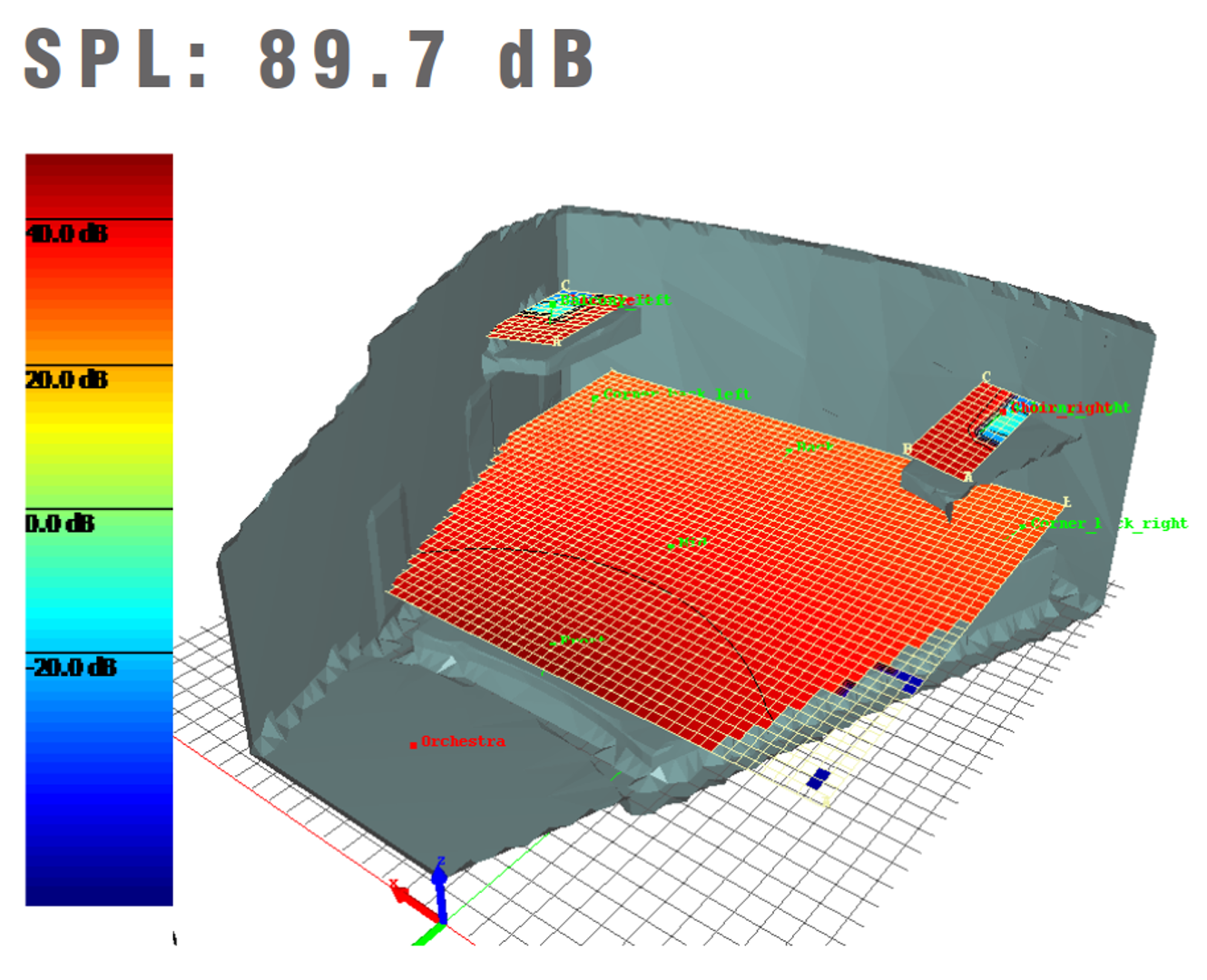

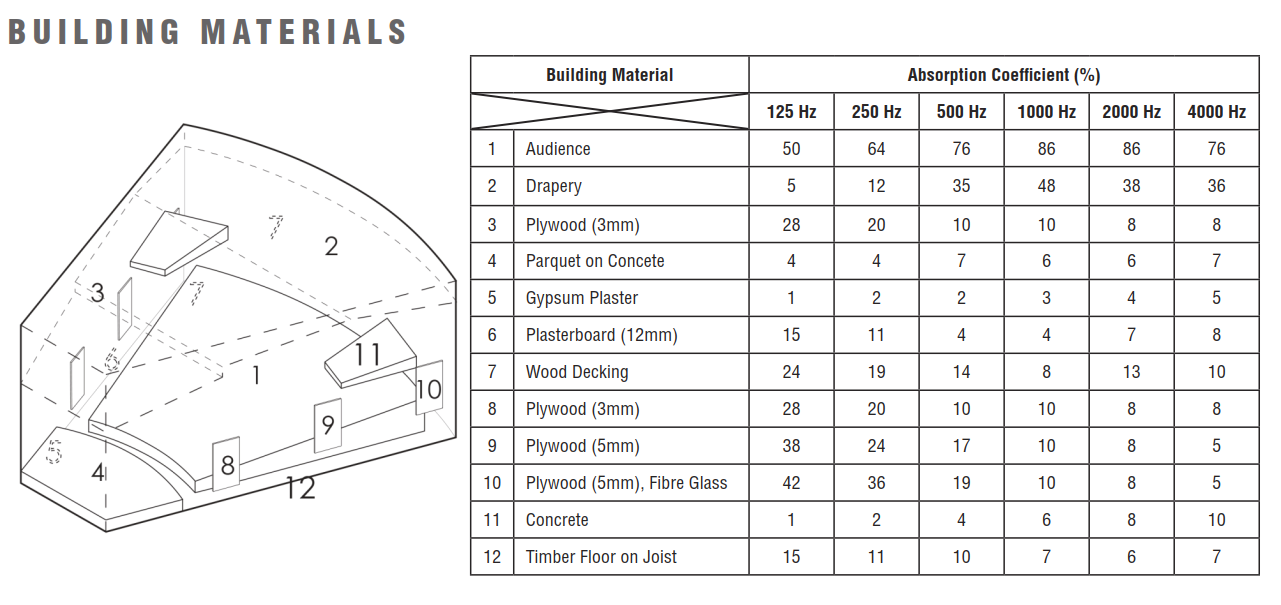

IntroductionThis theoretical design maximises enojoyment of Western Classical Period during the Late Romantic Period through application of Acoustics in Architecture. After establishing the acoustic parameters, the designs are then simulated through I-SIMPA, which models sound propagation in 3D spaces to build towards the Optimal Concert Hall comprising of a band for 100 musicians.

Design DriversAcoustic parameters drive the iterations of the designs, taking into consideration the most desirable Sound Pressure Level, Reverberation Time, Clarity and G-Strength for an optimal Concert Hall for Western Classical Music of the Romantic Period.

Parameters Objectives- Sound Pressure Level (SPL): 80dB - 90dB

- Provides adequate loudness throughout the concert hall.

- Reverberation Time (RT60): 1.8s - 2.2s

- Smooth decay of sound for envelopment of music. This offers ample 'room' that imparts on listeners a sense of acoustic space.

- Clarity (C80): - 2.0dB

- Enables listeners to follow the melody while distinguishing the bass during rapid musical passages.

- G-Strength (G): 4dB - 7.5dB

- Ideal balance between direct and reverberant sounds.

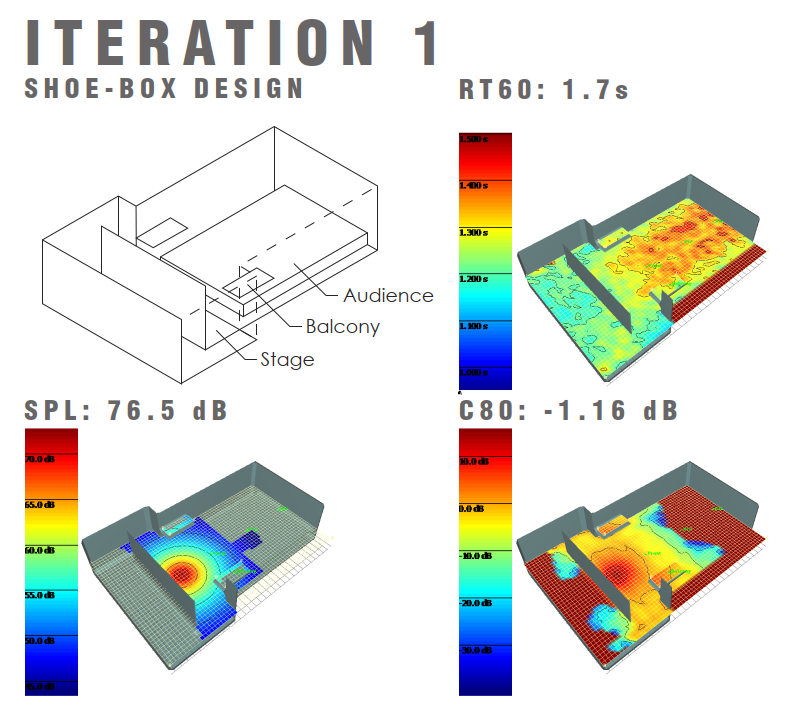

Iteration 1Starting simple, Iteration 1 was shoebox-shaped with 2 balconies flanking the sides to quickly meet the space requirements of the brief.

-

SPL: 76.53dB

- Lower than the minimum range set for the SPL criteria.

- A low SPL meant that the reach of the sound does not extend to the entire concert hall.

- RT60: 1.7s

- Missed the mark by 0.1s.

- SPL at 1.5s and 2s is extremely low.

- Only some areas in audience reach an RT of 1.5s, but not higher than that.

Conclusion: Primary Criteria not met, undesirable.

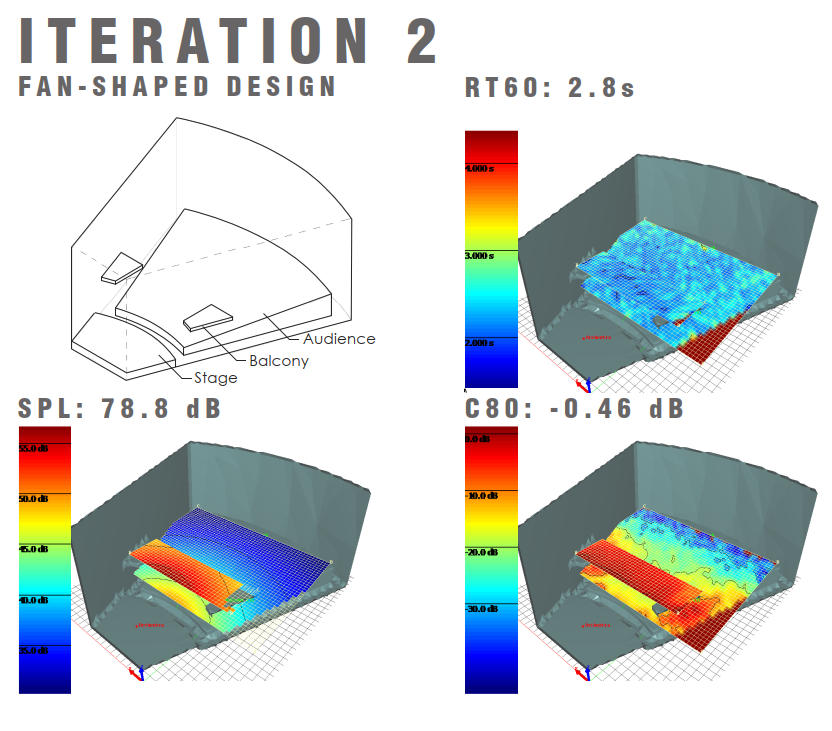

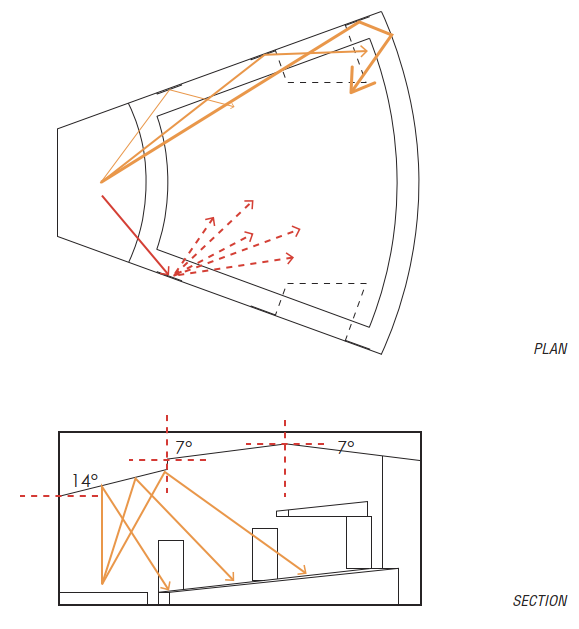

Iteration 2Theoretically, fan-shaped spaces lengthens RT due to early reflections being produced later. Height of Concert Hall was doubled to further increase RT based on Sabine’s reverberation time equation. Walls were also designed to be concaved to prevent fluttering echoes and standing waves. The audience seating was also angled at an ideal angle of 6 degrees to increase the direct sound pressure received at some distant seats.

-

SPL: 78.84dB

- Slight improvement from Iteration 1.

- Reach of sound extends to entire audience.

- Still lower than the minimum range set for the SPL criteria.

- RT60: 2.8s

- Some sound reflections after 2.0s.

- C80: -0.462dB

- Music is clear near the stage.

- Sound decays gradually to the back of the concert hall.

- Some Clarity for music is obtained.

Conclusion: Results have improved from Iteration 1, but still do not meet the crtieria. Undesirable, despite fair Clarity.

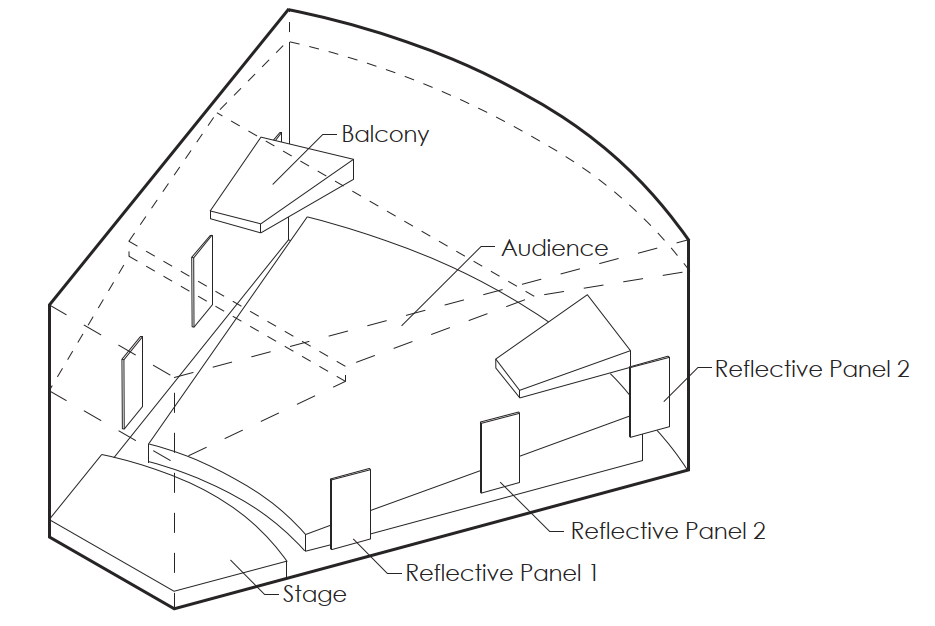

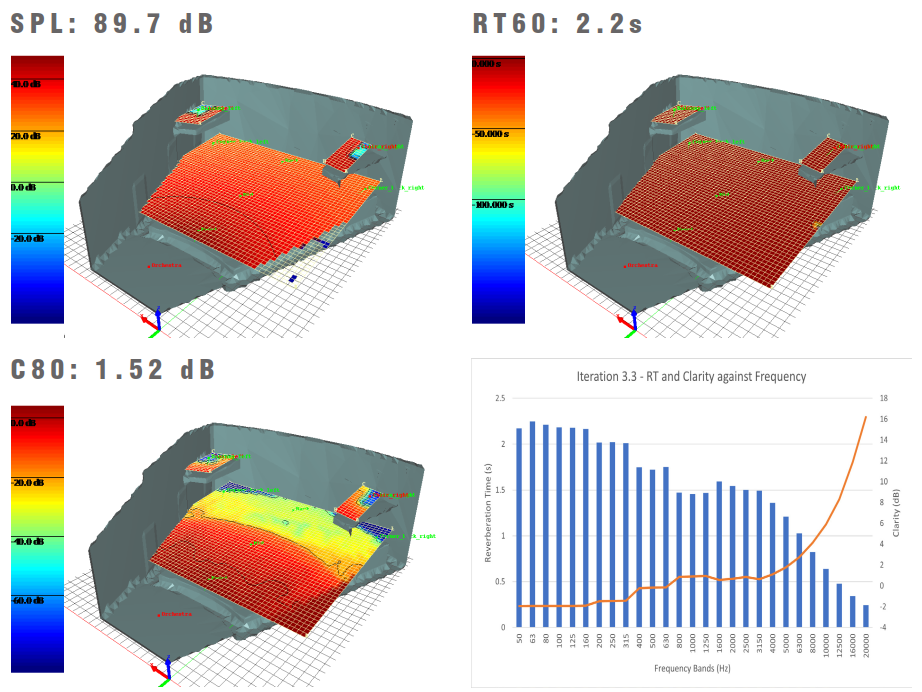

Iteration 3 (Final)3 more Iterations within Iteration 3 were produced, eventually reaching the final design worthy of an Optimal Concert Hall. The ceiling was further separated into 3 different profiles, each with a different sloping angle. This aims to lengthen the early reflection timing of sounds to achieve a longer RT. 6 Reflective panels were also added to the side-walls to provide better control over materiality within the design. Materials based on their sound absorption levels were also considered.

-

SPL: 89.67dB

- Reach of sound extends to back of audience.

- Within range of SPL criteria.

- RT60: 2.2s

- Most audience spaces distributed with RT of a higher sound power gain.

- Good RT distributed across entire audience seating.

- More consistent frequency response in the presence of frequencies with a gentler roll-off in the air frequencies.

- C80: 1.51dB

- Similar to other iterations

- Good Clarity for music is obtained.

- G: 4.19dB (Front) / 8.36dB (Back)

- According to Beranek (2011), an increase of 1.0dB does not create a signifant change in perception of loudness of sound.

Conclusion: Achieved standards required for Concert Hall based on all criteria. This unique effect of warm RT with longer RT for lower frequencies, along with relatively higher Clarity for higher frequencies makes this concert hall stand out from other designs as it focuses on brighter RT and Clarity for audience to appreciate the melody at higher frequencies.

Further Analysis: Tackling Structural-borne and Adjacency Sound IsolationA “box in a box” design is proposed.

Important spaces are enveloped in multiple layers of insulation, such as air and rigid structural walls to elimiate vibrations from affecting the hall. This reduces background noise within important spaces.

Flooring is separated from structural elements and spaces between floor plate and concrete floor is filled with Vibration Insulator Peoprene Pad.

Further Analysis: HVAC Control Design to reduce mechanical noise interferenceTo reduce mechanical noise frmo interfering with the music, HVAC room location should be next to any “Storage Space”, which is a non-sensitive, buffer space. Spaces surrounding the HVAC room dampens the mechanical noise.

The HVAC room should not be located disparately far from the Concert Hall so that high air velocity is not required to supply cool air into the large hall, therefore effectively reducing the duct size further. With lower air velocity and smaller duct sizes, the ‘rumbling’ mechanical sound is reduced.

In collaboration with Joachim Navarro (NUS, YST), Justin Ong (NUS, DOA) & Xia Yixuan (NUS, YST) Bridging

Bridging Introduction

Introduction

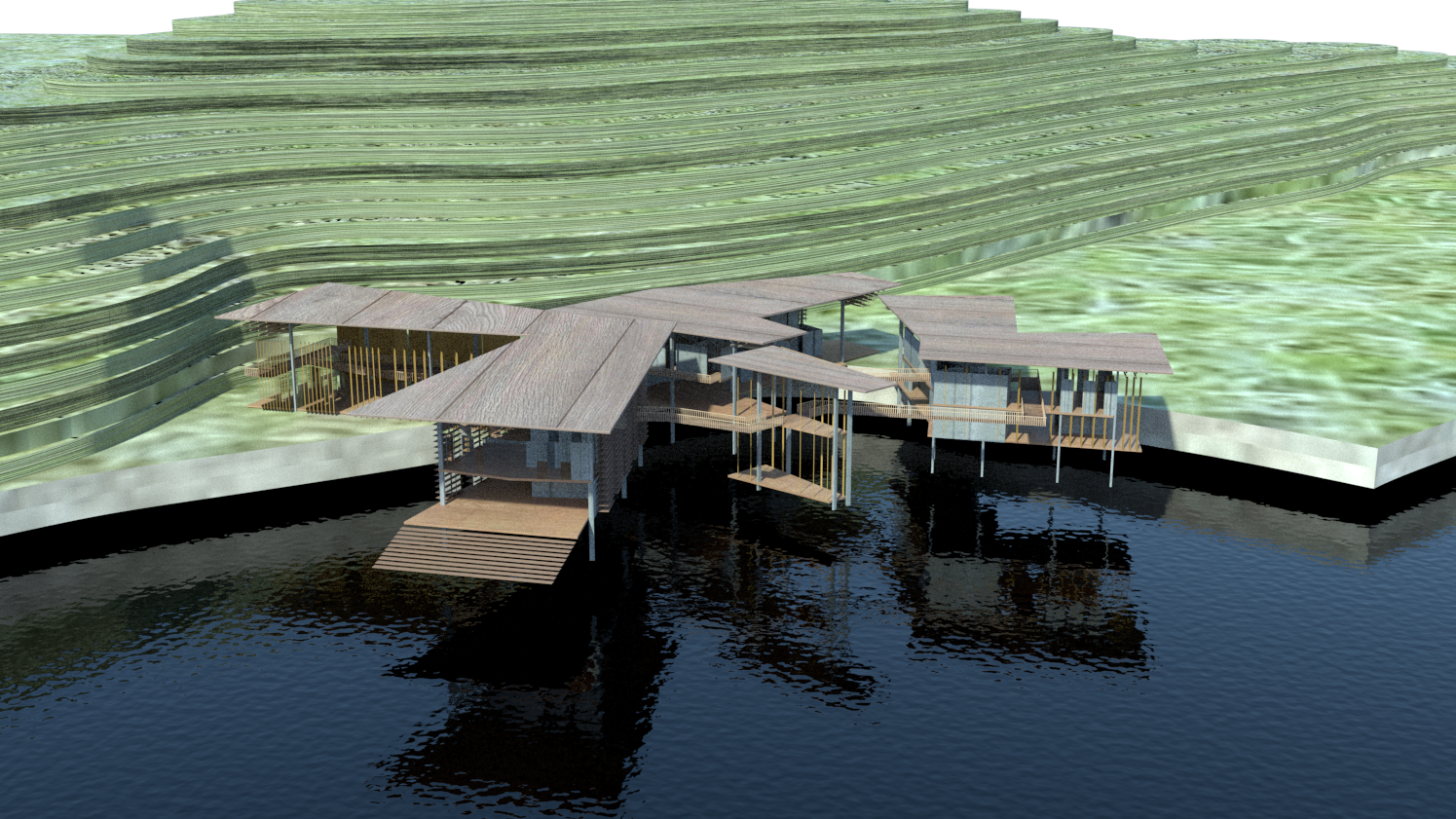

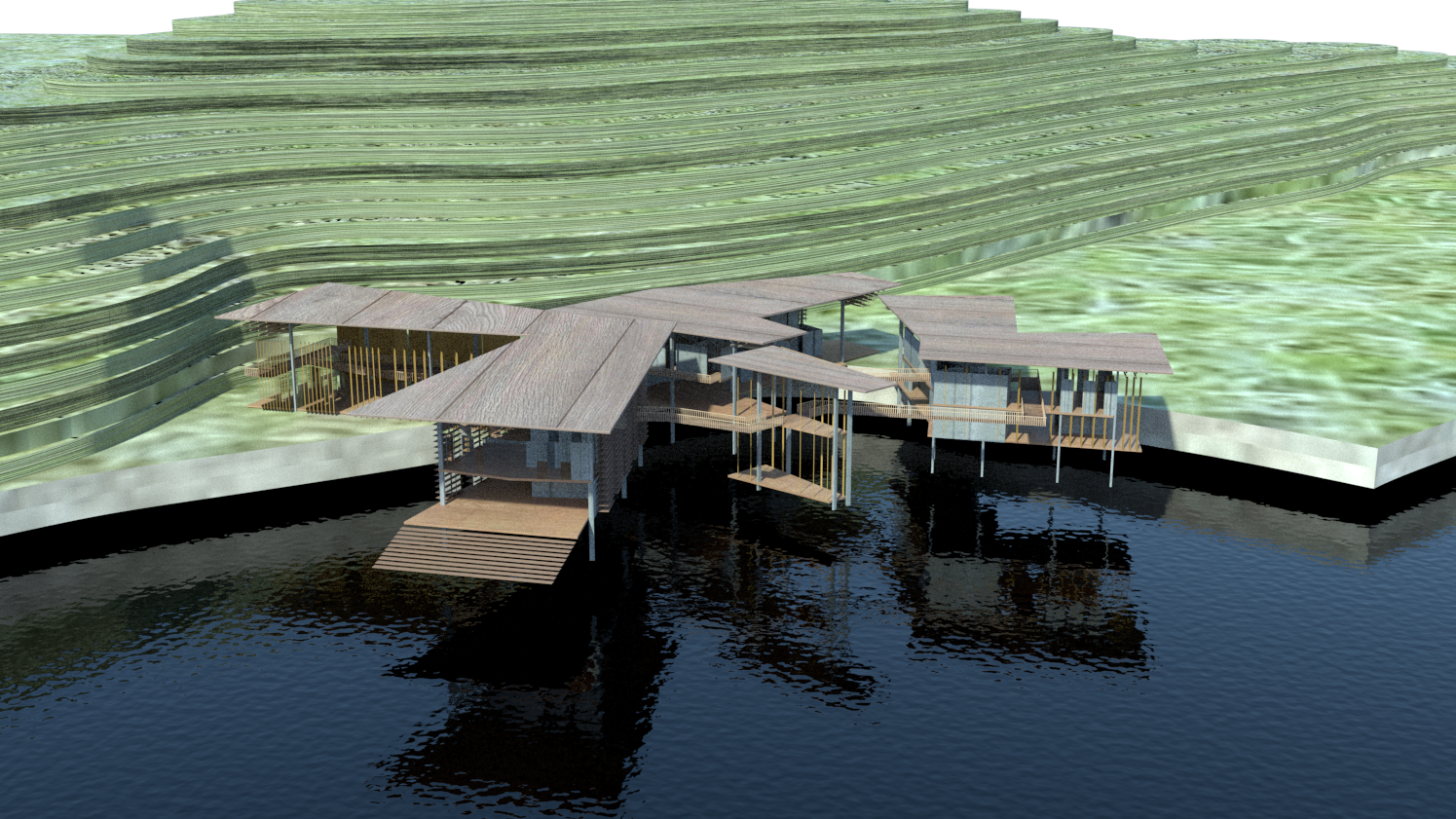

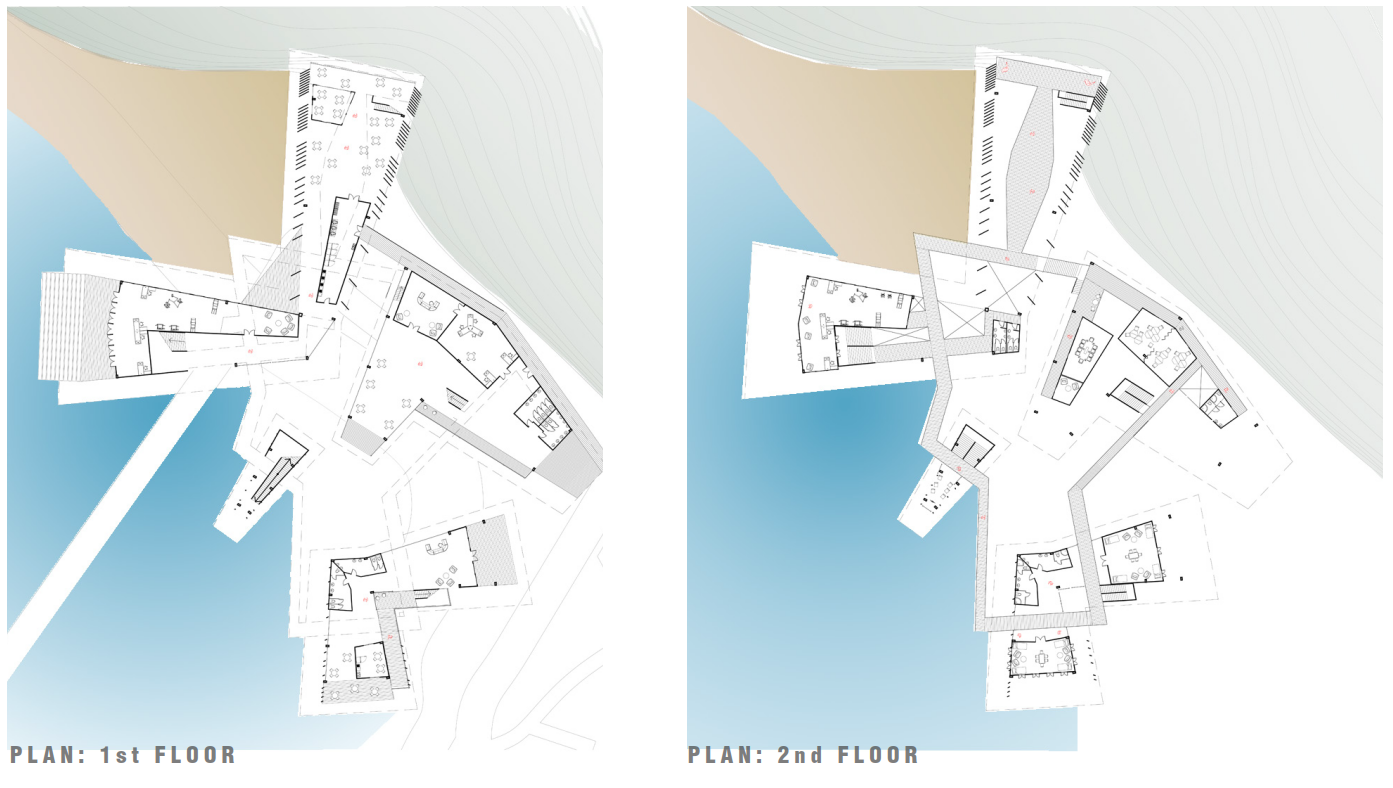

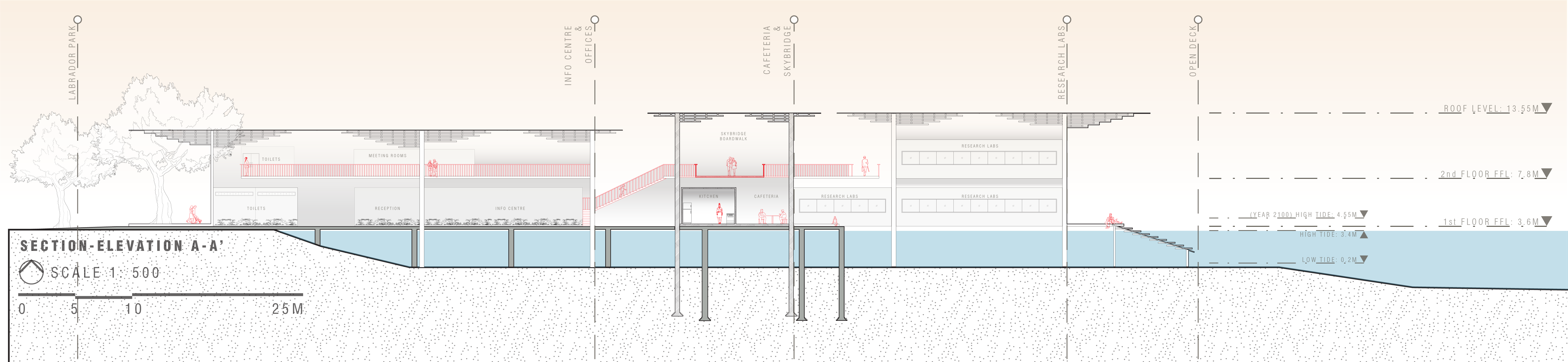

Situated on the abandoned jetty at Labrador Park, the plot is surrounded by a unique combination of environmental conditions, being at the transitional zone between land and sea. A Mixed-Use Building comprising of a Marine Biology Research Lab to study the Intertidal zone, a Researcher’s Villa and a Nature Trail is proposed to promote further research in Environmental Sciences via the labs and to spread environmental awareness via nature trail. The inclusion of the Nature Trail is also an attempt to ‘return the space’ from privately-owned buildings back to the public.

Design Drivers

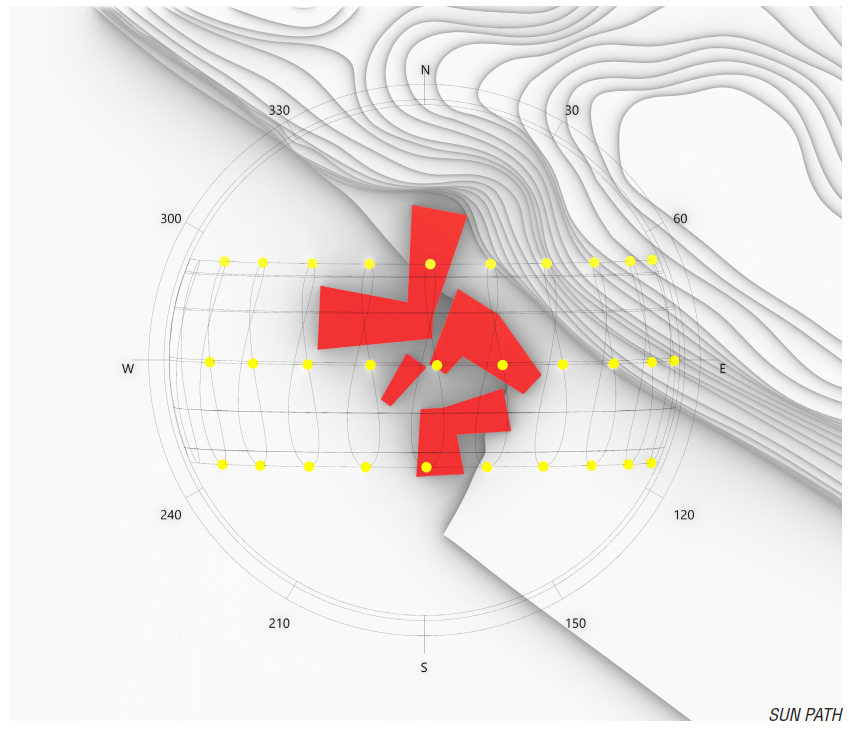

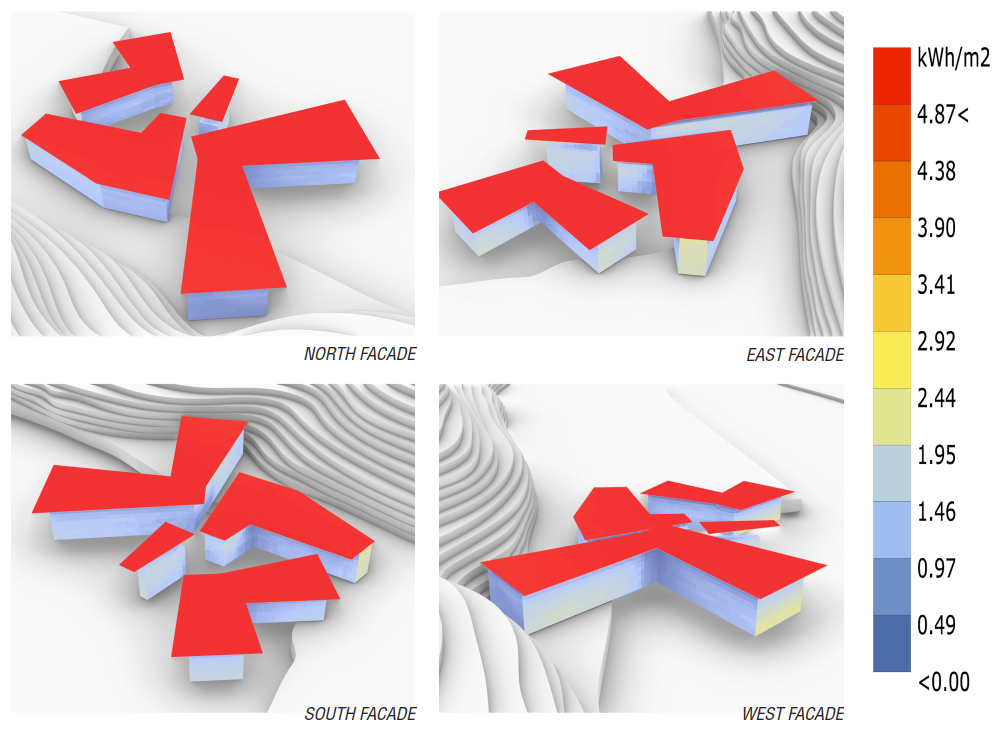

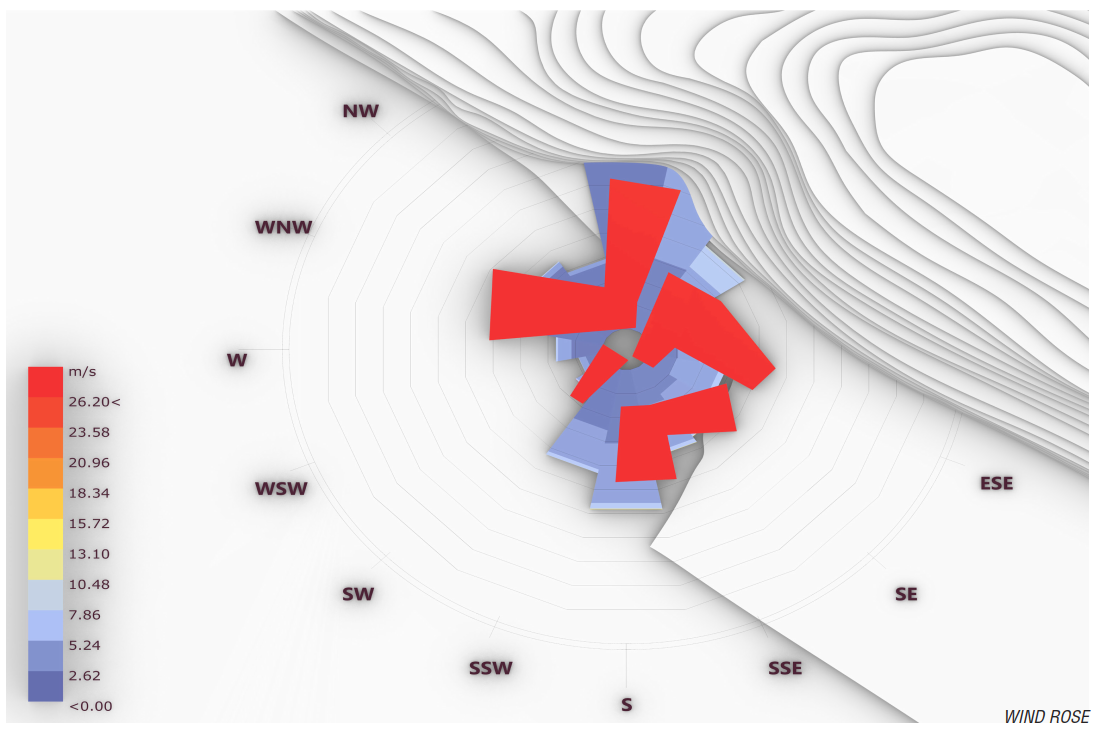

Aligning with the core Environmental Value, the design aims to be environmentally sustainable. It is primarily driven by capitalising on the tropical climate while minimising carbon production during its building lifecycle. This core value impacts the massing, building envelope, circulation from the interplay between public and public spaces, down to mechanical and electrical strategies employed, through environmentally sensitive and data-driven approaches.

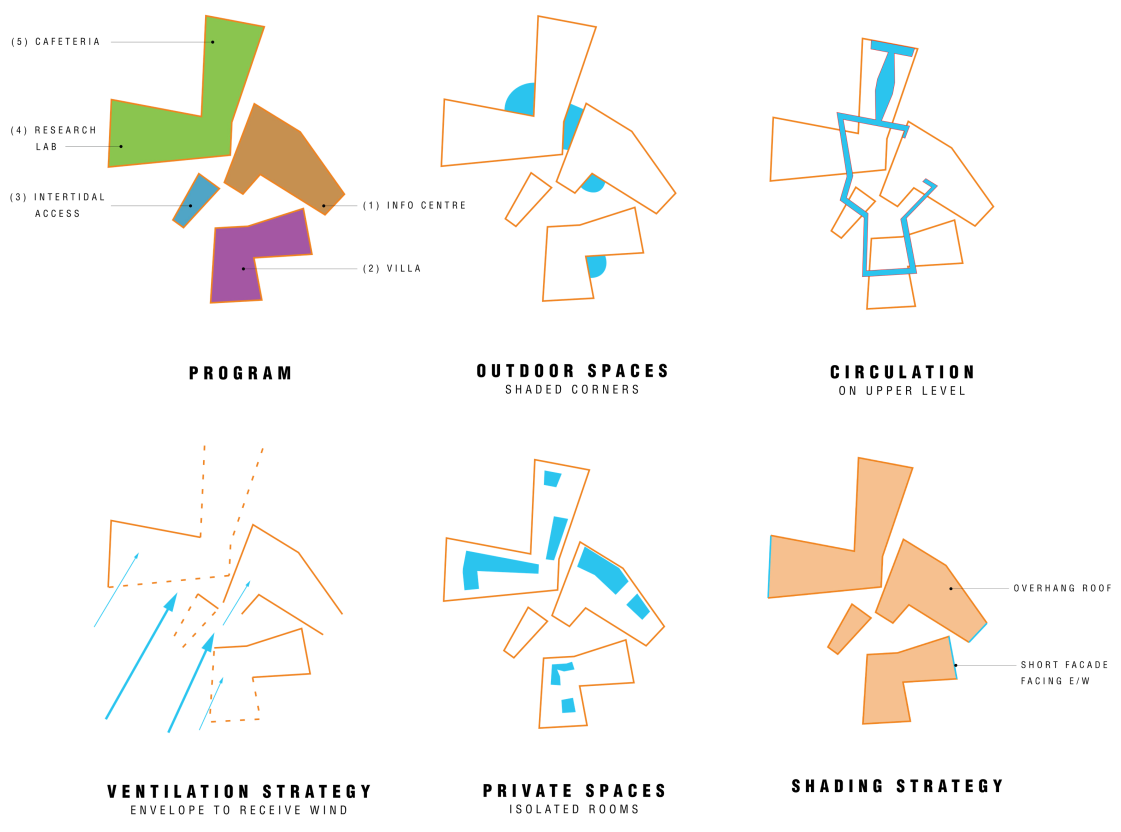

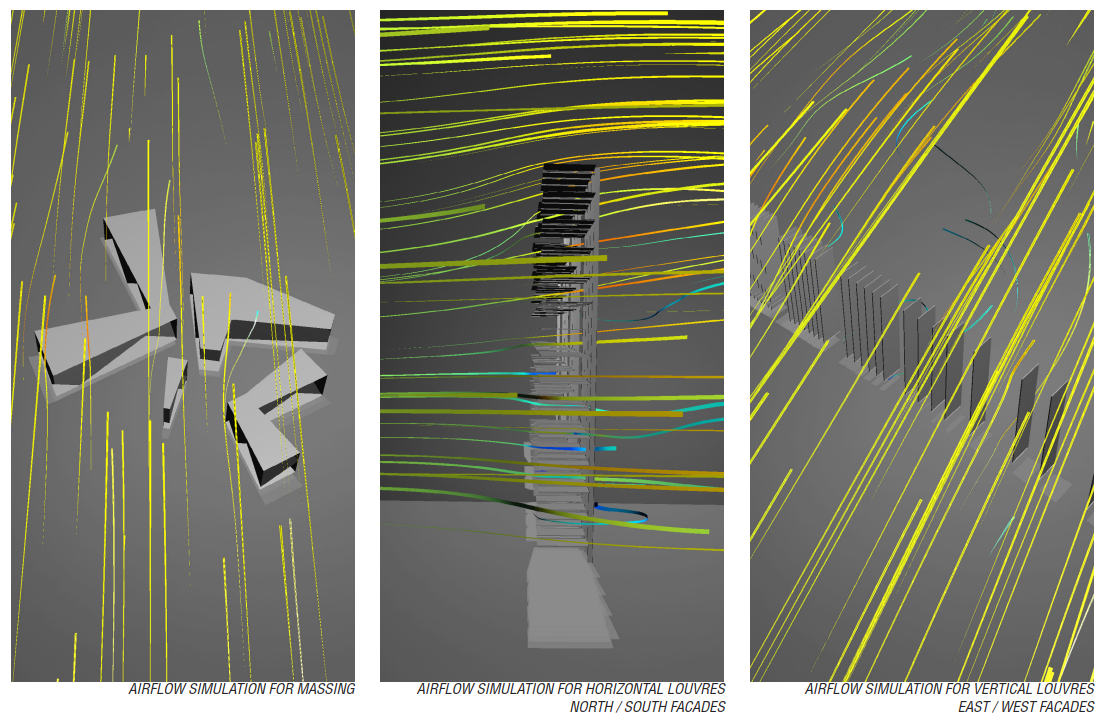

Massing and CirculationThe Massing comprises of 4 separate sections - Information Centre, Villa, Intertidal Access and Research Labs with a shared Cafeteria. All the massings employ a similar shape, with the large volumes on both ends tapering inwards and connecting with a kink in the middle. Using digital simulations, such massings and its arrangements provide ample shading and harnesses the ‘Venturi Effect’ for ventilation.

Floor Levels of each massing is also conscientiously decided so that the spatial experience with the building and the environment dynamically changes as the wave height fluctuates. For example, a staircase shaft leading to the Intertidal Zone on the shore-bed would be flooded during the high tide, while users at the outdoor decks can experience activities next to the sea as the tide rises.

Being cognisant of private spaces such as the research labs and offices, the design seeks not to forcefully segregate zones, but to consider possibilities of co-sharing the building footprint and creating autonomy to access all buildings. A skybridge is proposed as an integral element to the circulation solution, which connects the four distinct massings on the upper level, while retaining the pirvacy needed in spaces on the first level. Through this skybridge, individuals are also taken through ‘portals’ to enter into the outdoor scenic - a breathtaking view suspended over the southern sea - and completing their trail with a close-up view of Fort Pasir Panjang.

Construction MethodsThe design further considers green construction as part of Architectural sustainability. The abandoned jetty is adaptively reused as the primary structural element, while the remaining building load is distributed with stilt-like piles planted into the seabed, loosely replicating South-East Asian fishing ‘kelongs’. These slender piles reduce the concrete footprint on the seabed.

Architectural PoetryThe 1st Floor Level approximately matches the highest tide of Year 2019 when the design was conceived. It serves as a marker of time and the current state of our environment before its plight progressively deteriorates. The implicit message of Bridging is insidious - Global Warming leading to extreme sea level rise is inevitable, and generations will look back at this building and go, “This was where it started, the beginning of the end”.

Studio: NUS Year 2, Semester 2, Dr. Yuan Chao.

Studio: NUS Year 2, Semester 2, Dr. Yuan Chao. Tropical Primitive Hut

Tropical Primitive Hut Introduction

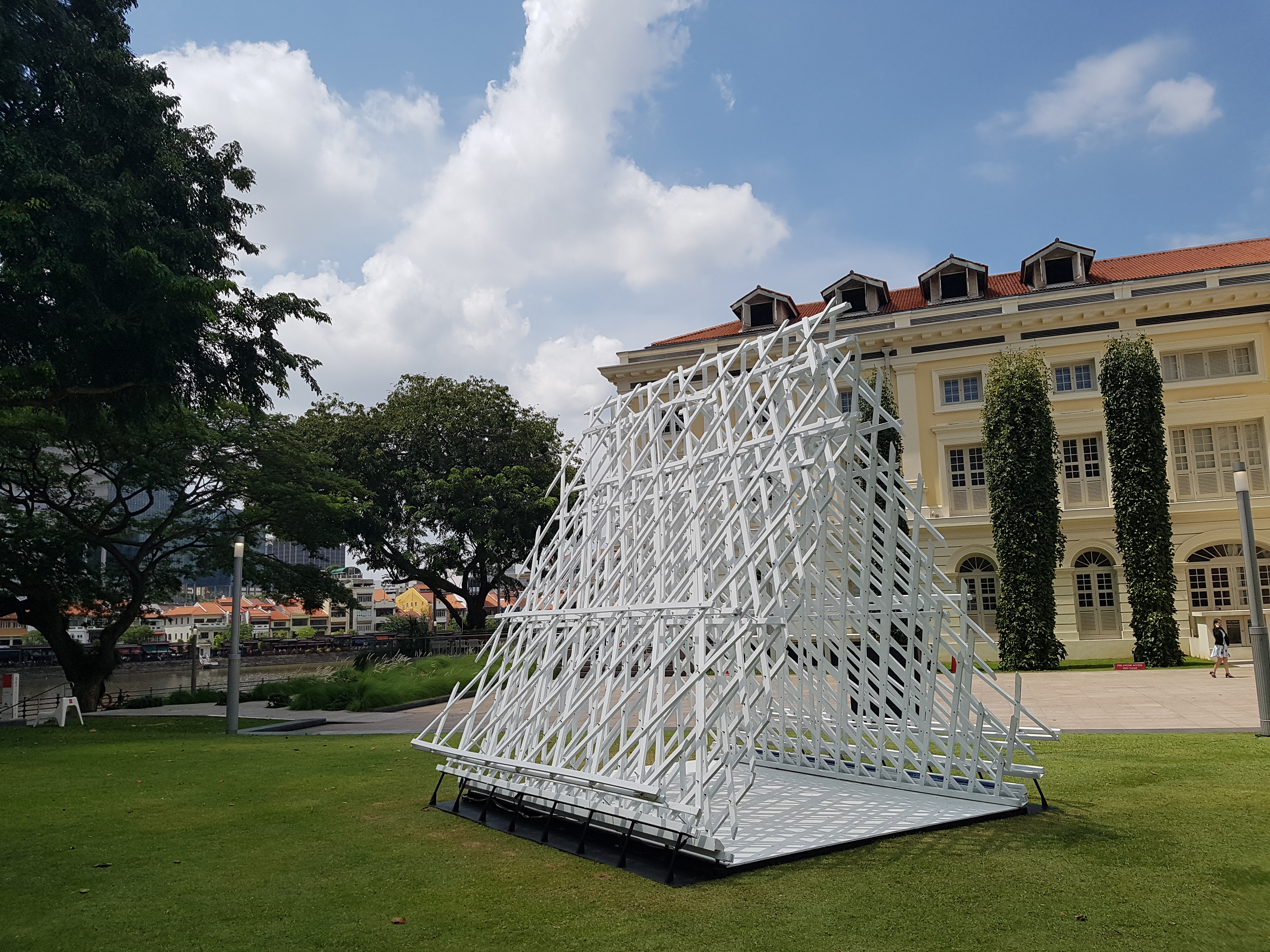

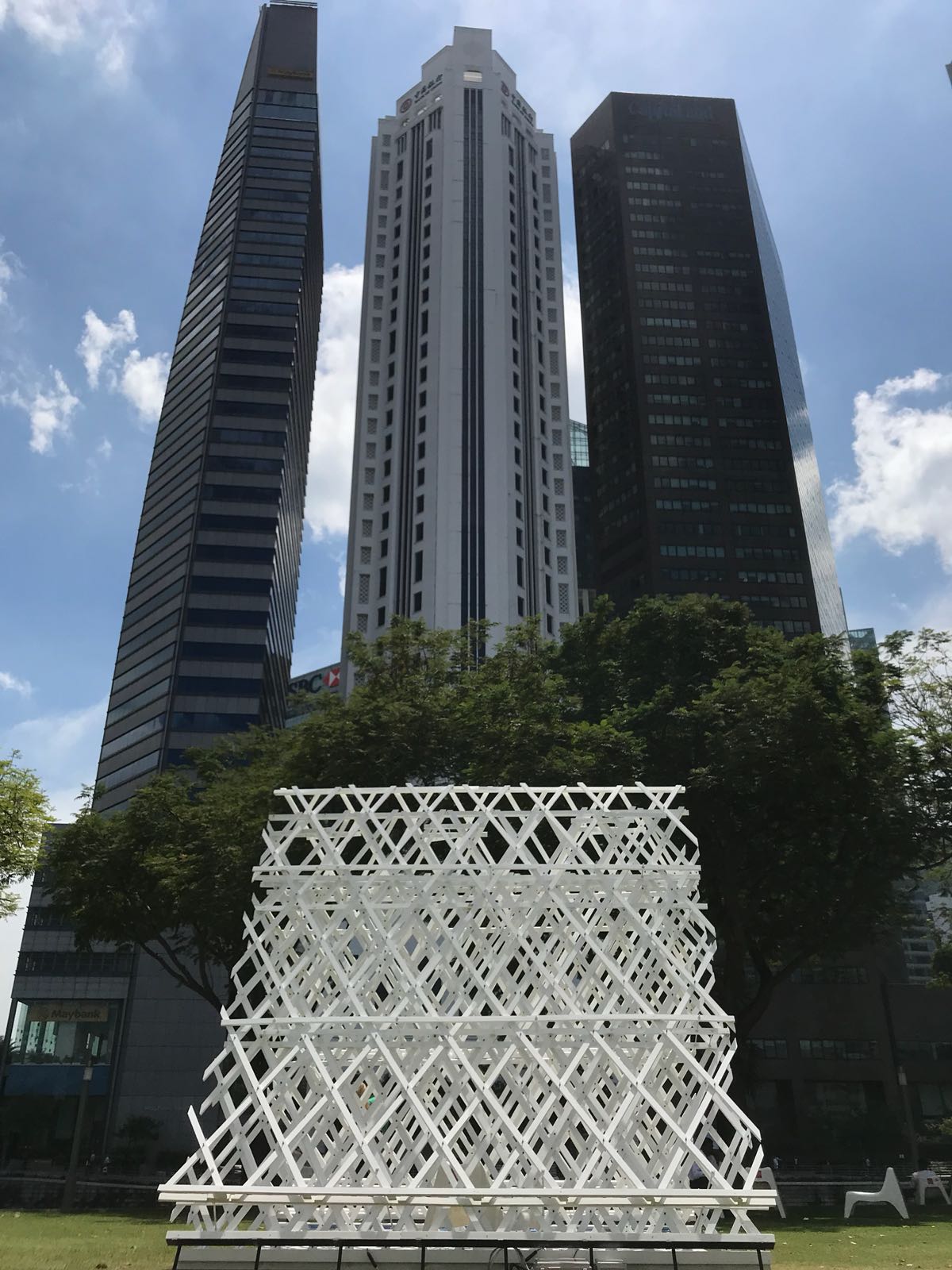

IntroductionShowcased at the “Light to Night Festival” in 2018, this temporary folly displayed in front of the Asian Civilisation Museum stole the spotlight with its tropical design and lighting effects. As part of the National University of Singapore’s Architecture Year 1 Semester 1 Design cirriculum, the brief was to design a folly which demonstrated strong understanding of “Tropicality”, with further consideration of light and shadow play. The “Tropical Primitive Hut” was conceptualised and designed together with studiomates, Anna Cao, Fasihah Bte Mohamad Azhar, Irfan Dinnie Bin Zaihan, Joel Ng, Leow Xing Ni, with guidance from studiomaster, AR. Ng Sanson.

Design DriversInspired by the cloud’s relationship with the elements, such as the Sun, wind and rain in the tropics, the genius loci of this folly stems from a single hexagonal module tessalated into a lattice to form its envelope. Like how clouds layer upon each other to change its density, further influencing shading, wind and rain patterns, each layer of the envelope moving away from the centre becomes denser and less porous to mimic this relationship.

While maintaining the sense of safety one experiences from the elements by standing under the folly, this Tropical Primitive Hut was reinterpreted in today’s urban context to embrace the natural elements unique to the tropics, instead of rejecting them entirely.

This re-conceptualisation of Tropicality hoped to foster an intimate relationship between urbanites and the tropical climate.

Architectural Poetry of LightCool-white LED strips lined the base of the folly, facing upwards intentionally to provide the illusion of the hut “floating” above the ground.

While the entire timber structure was painted white, the singular cool-white light accentuated this glow effect radiating from within.

Finally, this modest hut surrounded by the excessive display of colours and lights around the business district served as a resting point for all the visually overstimulated. They could always recover some tranquility and stillness from this gentle and unassuming pavilion grounded in the centre of the towering skyscrapers.

In collaboration with NUS Arch Y1S1 (AY2017/18) studiomates: Anna Cao, Fasihah Bte Mohamad Azhar, Irfan Dinnie Bin Zaihan, Joel Ng, Leow Xing Ni, with guidance from studiomaster, AR. Ng Sanson.

In collaboration with NUS Arch Y1S1 (AY2017/18) studiomates: Anna Cao, Fasihah Bte Mohamad Azhar, Irfan Dinnie Bin Zaihan, Joel Ng, Leow Xing Ni, with guidance from studiomaster, AR. Ng Sanson.

With support from other studiomates: Leong Siew Leng, Nigel Chew, Rafael Tan, Winston The, Wong Shinyin, Zheng Liying.WritingQuiet Thoughts

Sort by-

My Road Less Travelled

#Reflections #GrowthMy Road Less Travelled#Reflections #GrowthI have been struggling with my professional identity for almost a decade now. In the height of that low, I quit my job and took an indefinite break from Architecture. This is my Road Less Travelled, and my identity in the making.

On detracting from the familiar

There are expressways that take you to your destination efficiently on the straight, fast-moving path. There are also winding roads that you need to traverse to take you to the summit of a mountain. Expressways are familiar and certain. Winding roads are not. Perhaps that is why people tend to take the straight road forward. I was no exception.

I studied Architecture at a college that was ranked 9th in the world. An Architect’s path was straightforward. It was certain. It was familiar. The ride was smooth-sailing till I made a small deviation in this chartered route.

I questioned a professor.

His methods were ineffective to the new generation but he wasn’t receptive to alternative techniques of teaching. I silently protested, refusing to validate his methods even when seniors advised that his class was an easy ‘A’ if I blindly followed his designs.

Something in me just could not agree with that lack of ownership in my learning. Eventually, I changed tutors, pulling out of his class entirely.

That event opened my mind. It was like getting off the highway with no way back. I got out of my comfort zone. I detracted from the familiar. I started critically questioning norms and processes. That was when my learning truly began.

On seeking growth in radical ways

Architecture education is in need of a dire reform — that is a discourse for another time. I came to that conclusion during my 3rd year of undergraduate studies and through observing young practitioners in the industry. I wanted to be a better Architect and Designer. However, I knew that I wasn’t going to achieve that by taking the straight path forward.

So I did what most Architecture students would not dare do.

I worked as a Main Contractor.

My first job after graduating was with a Main Contractor building public housing during the COVID-19 pandemic. I was working out of a container office on-site to coordinate building works.

It was a huge leap to pursue this professional growth. My methods were radical.

I declined a standing internship offer at a prestigious boutique Architectural firm. That meant giving up the opportunity to be mentored under an Award-winning Architect running a successful practice.

I graduated a year earlier than my peers without completing my Master’s degree in Architecture. That meant entering the industry without the necessary paper qualifications to take the Board of Architect’s licensing examinations.

These sacrifices were painful but needed. I left a system that overtly emphasised on theory, aesthetic design and efficient production, where I could not learn more from, for an environment which mandated strong technical knowledge from various disciplines with soft skills necessary to design, manage and complete construction projects.

To me, that was understanding the reality and technicality of building-design. It was understanding the perspectives of every player part of this complex network and it was leading the design and construction of buildings. To me, it was being a better Architect.

My methods were radical but extremely effective. However, that meant driving up the dirt road instead of the paved one, into the forest without a clearing in sight. That was just the beginning.

On stress-testing to failure to identify limits and assumptions

Steering off-course meant driving without institutional regulations. There were no standardised indicators of success; no instructor to keep you grounded and accountable to the destination. You are your own captain. Thus, I needed my own indicator of success.

In construction, one of the most effective ways to determine the strength of a material is to test to failure — stressing the object till it breaks. The same can be applied to skillsets and experiences. By increasing the intensity and load of my job scope, I identified my limiting potential and limiting assumptions of the craft that I have honed. I was fortunate to be offered such an opportunity.

I was head-hunted by a hotel developer to build an island resort in Australia.

This family-owned developer was seeking a Project Manager with Architecture and Building background to spearhead their newest project. Their business model tapped on specialised professionals to manage hotel developments in-house. This allowed them to keep their project cost low while internally controlling progress, quality and cost, by managing essential aspects of supply-chain, design and project management. My interdisciplinary edge developed during my construction days, legal background and youthful energy was a perfect match at that time.

It was the perfect environment for me to showcase these skills that I have honed during different stages of my life, be it my period of studies in Architecture and Law and my tenure in the previous construction company. Like me, the owners were stress-testing their abilities too.

During that period, I experienced the effectiveness of my unique leadership style which struck a suitable equilibrium between strategy and operations.

I became that leader I envisioned about. A leader who took-in considerations of the developer, consultants and contractors, and steered all parties towards the same goal. A manager who could communicate effectively and technically, while employing prophylactic strategies tailored to the project context. A mentor who developed the skills and knowledge of his lean team to support the project operations. I was unstoppable…

Until I failed. Scaling steeper mountains shattered several assumptions I had about this line of work. No matter how insightful or intuitive I might have been, I was still a paid salaryman. Bosses — and in my case, the land owners — had differing agendas. Approaches that improved the health of the project might not be aligned with the paymaster’s business goals. The ultimate decision-maker was still the master who fed, regardless of the servant’s cautionary advice.

This was when I had to confront the biggest limiting factor in my career — my fire-forged experiences could not hold up to a Master’s degree in Singapore. The local market placed greater significance on the Master’s of Architecture (M.Arch) certificate than actual work experience and exposure to related domains. Job offers were pulled immediately because this pre-requisite was not met, even though those job scopes did not require a Registered Architect’s license.

The walls were closing and the water level was rising. I had no means to break that career ceiling without attaining my M.Arch to perform in the role I was already excelling in. Simultaneously, I had no growth opportunities (and thus no incentive) to work a simpler role or even to return to earn the M.Arch — a course that doesn’t prepare me for the actual demands of practicing architecture more than I already was. This was the outcome of relentlessly stress-testing to failure. I identified this dead-end earlier in my career but I wasn’t going to halt anytime soon.

On owning my road

You would think that it would have been a more efficient use of my time to have just kept my head low and graduate with my M.Arch, when I had the chance. Stay on the express lane and not diverge from that smooth road that I was on. Afterall, it would be fairly manageable for a top student to complete the M.Arch course, where I was already acing the concurrent Master’s Year 1 curriculum and unfamiliar modules like ‘Architectural Practice’ — of which a huge part was on legal systems and building contracts — was known territory to me from my law education.

Believe me, I have lamented at every chance I had, at every job rejection I faced, at every rule restricting me from doing what I do best in the local construction scene.

And I did. Or at least, I did try to find my path back on that highway. I quit my job and steered my way back. I was grateful to be offered a chance to finally complete the M.Arch at another university… Yet Life had other plans. The result of a series of events over a short 3 months led to another divergence.

I ended up accepting another Master’s course. In Urban Sciences, Planning and Policy.

I was thrown off the high road once again. It seemed to be a pattern I cannot break. Then I finally understood, and after a decade of figuring out my professional identity, I came to peace with who I am.

Ultimately, it wasn’t about which road was better for my career. It was about which road was more suitable for me as a person. The path which provided the experiences I valued — challenging terrains, perspective-filled sceneries and fresh air, just like the winding mountain roads in Bhutan that I was on a week ago. Indeed, my journeys were exhilarating, from breaking fast with my construction comrades at the worksite to camping overnights on the abandoned island.

I shouldn’t be ashamed of my experiences when I share my story, especially with industry man and recruiters. Owning the road that I had taken, along with all those that I would take, would be to own my own value:

I am an Unfiltered Leader, unafraid to rise above the conventional when filtered leaders are tethered by rules and restrictions. Placed in the right ocean where I can be quiet, my best work emerges. My output is often holistically complex, yet executed in simple, structured steps. I value transparency and good faith, and this often places me at odds with upper management who may prefer cloak-and-dagger tactics to manipulate both the team and the mission. What drives me isn’t just professional integrity, but my unwavering belief in a cause greater than myself, and it is in this silent intensity where my leadership finds its truest form.

As like other Unfiltered Leaders who all took their own roads less travelled, I am, perhaps, simply not suitable for the roles commonly available in the job market. And accepting this is astonishingly liberating.

No more attempts to squeeze into a box that doesn’t fit. No more second-guessing the winding roads I am meant to travel on. I am not an Architect, nor am I a Lawyer. I am just someone taking a Road Less Travelled, modestly discovering the mysteries hidden in the corners of the world.

-

Towards a Compassionate City Urban Vision

#Compassionate Cities #Urban Visions #Palliative CareTowards a Compassionate City Urban Vision#Compassionate Cities #Urban Visions #Palliative CareIntroduction

Everyone dies. This is an inescapable fact we ignore, more so now as cities become more developed. Besides the cultural taboo and fear encompassing ‘death’1, medical technology has advanced to the point where “death and loss [are perceived as] ‘failures’ of health”2 . The main objective of “Compassionate Communities” – which transitioned into “Compassionate Cities” – as coined by Professor Allan Kellehear is to reframe our stance of death from “professionalization of death” to the re-introduction of community to end-of-life care3. This shift in perception has socio-economic benefits – alleviating the burden on public health institutions and improving quality of palliative care4.

The concept of “Compassionate Cities” becomes increasingly and urgently relevant to Singapore – a developed city with advanced medical technology – where “more than 20% of the population is expected to be 65 years old or older”5 by Year 2026. Despite the Ministry of Health’s (MOH) efforts to improve palliative care, as noted from Minister of Health, Ong Ye Kung’s, keynote address in Year 2023 and a more recent speech in Year 2025 where he outlined the “National Strategy for Palliative Care”6, these policies may be viewed as institutionally reliant and holistically fragmented without much integration of the larger urban community.

The literature hints that there may be potential to enlarge the scope of “Compassionate Cities” beyond a palliative care framework by articulating it as an Urban Vision, situating end-of-life care within broader theories of urban strangers7 and conflict8. By unpacking these concepts through the “Compassionate Cities” urban vision, it becomes possible to strive towards a true community-based care which goes beyond public or institutional-based care. A city where kindness is not limited to a professional capacity.

Reinterpreting Compassionate Cities as an Urban Vision

Dying in contemporary society is structurally complex due to how end-of-life is organised and experienced within modern urban systems. The challenges surrounding institutionalised dying intersect multiple sectors including healthcare, labour, housing and economics. On the other hand, the experience of dying is shaped by conflicting values such as empathy, dignity, autonomy and efficiency. Interventions in one domain inevitably generates consequences in other domains and there is no singular solution to this social issue. More fundamentally, dying is a phenomenon which none can escape from. This process is experienced by all urban residents when they approach the end of life. Others may experience this process multiple times embodying different roles, including a caregiver or family member supporting other individuals at the end of life, or as a member of a wider social network who provides indirect support to these other individuals at the end of life. Death itself is not the problem. The institutionalisation and “professionalization” of death – in which care, responsibility and resources allocated around the end of life – is a “wicked problem” as coined by Rittel and Webber in 19739.

The values underpinning end-of-life care as a broader Urban Vision can be examined through urban theories of strangers and conflict. As put forth by Bauman in 2016, contemporary societies observe a gradual desensitisation of empathy that is the “constriction of … moral obligations”10. His concept of “adiaphorization”11 – the process of systematically dehumanising specific groups of people to justify one’s moral blindness towards them – may also be extended and applied in the context of patients on palliative care. “Adiaphorization” can operate on multiple levels. At the individual level, it may manifest as a gradual moral disengagement from the aged community – of which constitutes a large proportion of the city’s population – through the shift towards institutionalised healthcare. At the institutional level, it may take the form of policy shifts which distances responsibility of care. In analysing the dangers of “adiaphorization”, Bauman reflects on morality within the urban context and urges the reclamation of moral responsibility towards the “Other”12. Applied to this Urban Vision, this perspective frames palliative care as a collective moral obligation towards the aging population.

However, as “Compassionate Cities” become a collective urban vision, a focus on this group of individuals on palliative care generates agonistic conflicts within the city due to competing interests for limited resources13, including land, labour and public capacity. The answer to reconciliating these conflicts may lie within an extension of Chan and Protzen’s “integrative compromise” and “distributive compromise” theories. As postulated by the authors, “integrative compromise” involves “narrowing the difference” while “distributive compromise” involves “splitting the difference”14. Within the proposed “Compassionate Cities” framework, resolution of conflicts may be approached from a temporal lens. Instead of framing compromise as negotiation between competing individuals over finite resources, this essay proposes a form of temporal compromise in which trade-offs are negotiated within the same individual across time – by either “narrowing” or “splitting” the difference between present and future selves. In its most transactional form, conflict is addressed through “temporal distributive compromise”, whereby individuals accept present sacrifices, such as reductions in space or increased taxation, in exchange for anticipated future benefits, including access to palliative care and support at the end of their lives. In contrast, at its most solidaristic form, individuals “narrow the difference” by recognising ethical and affective values gained through indirect participation in the palliative care and support of other individuals. This “integrative compromise” may be argued as temporal in nature as the benefits gained from this approach may span across one’s lifetime.

Through groundings in urban theory, the relevance and urgency of “Compassionate Cities” as an Urban Vision may be further established. This allows further discussions extending beyond healthcare to the larger urban scale while providing a conceptual basis for addressing the conflicts that such a paradigm shift entail.

-

James Gire, “How Death Imitates Life: Cultural Influences on Conceptions of Death and Dying,” Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 6, no. 2 article 3 (2014). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1120 ↩

-

Allan Kellehear, interview by Singapore Hospice Council, “An Interview with Professor Allan Kellehear,” Singapore Hospice Council, August 13, 2025, https://www.singaporehospice.org.sg/an-interview-with-professor-allan-kellehear/ ↩

-

Allan Kellehear, Compassionate Cities: Public Health and End-of-Life Care (Routledge, 2005), ix. ↩

-

Kellehear, Compassionate Cities, 12. ↩

-

Deborah Lau, “How Singapore Is Preparing for a Super-Aged Society Come 2026,” Channel News Asia, October 5, 2024, updated October 8, 2024, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/today/big-read/super-aged-2026-singapore-ready-4656756 ↩

-

Ong Ye Kung, “Speech by Mr Ong Ye Kung, Minister for Health and Coordinating Minister for Social Policies, at the Launch of the Digital Advance Care Planning Tool,” Ministry of Health (Singapore), July 19, 2025, https://www.moh.gov.sg/newsroom/speech-by-mr-ong-ye-kung–minister-for-health-and-coordinating-minister-for-social-policies-at-the-launch-of-the-digital-advance-care-planning-tool/ ↩

-

Zygmunt Bauman, Strangers at Our Door (Polity Press, 2016). ↩

-

Carolina Pacchi and Gabriele Pasqui, “Urban Planning without Conflicts? Observations on the Nature of and Conditions for Urban Contestation in the Case of Milan,” in Planning and Conflict: Critical Perspectives on Contentious Urban Developments, ed. Enrico Gualini (Routledge, 2015), 79–98, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203734933-7. ↩

-

Horst W. J. Rittel and Melvin M. Webber, “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,” Policy Sciences 4, no. 2 (1973): 155–169, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730 ↩

-

Bauman, Strangers at Our Door, 80. ↩

-

Zygmunt Bauman, Modernity and the Holocaust (Polity Press, 2013). ↩

-

Bauman, Strangers at Our Door, 82. ↩

-

Pacchi and Pasqui, “Urban Planning without Conflict? Observations on the Nature of and Conditions for Urban Contestation in the Case of Milan,” 82. ↩

-

Jeffrey Kok Hui Chan and Jean-Pierre Protzen, “Between Conflict and Consensus: Searching for an Ethical Compromise in Planning,” Planning Theory 17, no. 2 (2018): 174, https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095216684531. ↩

-

-

Prospect Theory applied to BTO housing market

#Housing Policy #Citizen BehaviourProspect Theory applied to BTO housing market#Housing Policy #Citizen BehaviourIntroduction

“Will you apply for a HDB BTO Flat with me?”

For most Singaporean couples, this question is synonymous with a marriage proposal. This social practice originated from an underlying housing policy where subsidised public housing units, also known as a Housing Development Board (HDB) flats, can only be purchased by forming a legal family unit. Due to the lengthy wait-time of developing residential housing, an essential process for most couples taking their first steps into planning for matrimony would also be to apply for a HDB Built-to-Order (BTO) flat from the government. The wait-time is further exacerbated by an over-demand and under-supply of HDB units.

However, the Kallang Whampoa BTO release in October 2023 had, by far, the lowest application rates of 1.11. While others may attribute it to dumb luck and randomised chance, I believed that a combination of rational and irrational human behaviour was very much at play, influenced by the “nudging” of state policies grounded in psychology theories. This essay strives to explore more regarding this phenomenon which lies in the intersection of housing policy and citizen behaviour through analysing HDB application rates throughout time from a psychology perspective.

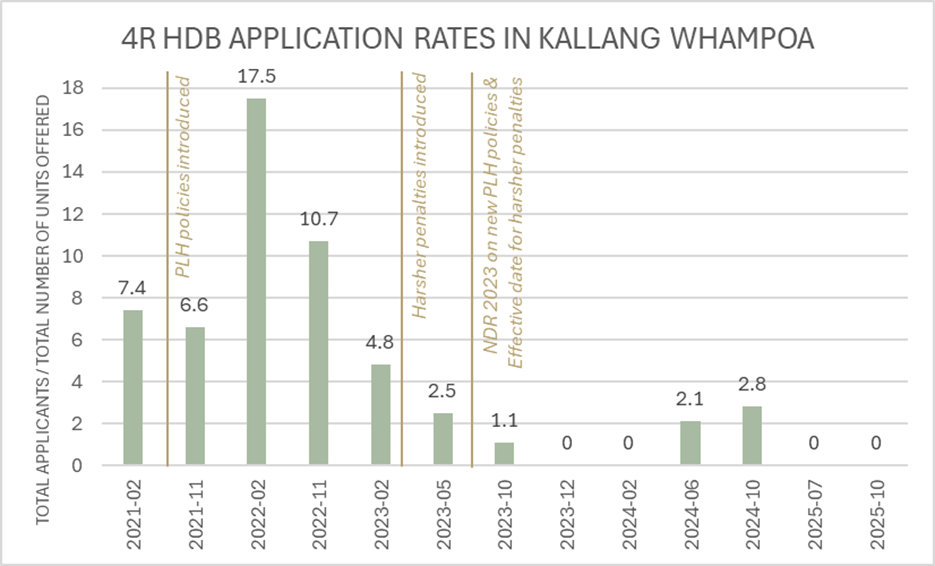

Fig. 1 – 4-Room HDB Application Rates in Kallang Whampoa from Year 2021 to Year 2025. Fig. 1 visualises the Application Rates of 4-Room HDB flats in Kallang Whampoa across the years, with essential policy changes reflected on the timeline as well. The data point highlighted in red (October 2023 cycle) represents the lowest application rate at 1.1 in a 5-year period, not withstanding specific application cycles with no Kallang Whampoa estate releases. Those application cycles therefore have an Application Rate of zero (0). This trend may be explained using a combination of theories, namely Prospect Theory and Recency Theory. It should also be prefaced at this stage that the data was collected from two secondary sources which had used different methods of calculation. Therefore, the data from Fig. 1 cannot be taken as precise but as a general understanding of BTO market trends.

Prospect Theory

A previous HDB policy before Year 2023 enacted penalties for applicants who were invited to select their choice of flat but forfeited their chance. This policy only applied to applicants who accumulated 2 counts of such non-selections, where these group would be considered as a “second-timer” for a year in the balloting system2. This greatly reduces the chances of securing a successful ballot as the number of units allocated for second-timers are much fewer as compared to the units allocated for first-timers. Specifically for the Kallang Whampoa selection by the end of October 2023, the percentage of 4-Room units allocated for “second-timers” was 5%3. However, in March 2023, HDB released an updated policy with harsher penalities rolled out to such applicants, reducing their non-selection threshold down to 14. The updated policy would be effective in August that same year. Through this policy, the government had attempted to tighten the BTO housing market by amplifying the effect brought about by the Prospect Theory introduced by Tversky and Kahneman in 19795.

In particular, the plummet in application rates in the October 2023 HDB balloting process may have been a result of a shift in matrix within the Prospect Theory, or Loss Aversion Theory. Prospect Theory states that “people are more sensitive to losses than to corresponding gains relative to their current reference point”6. Therefore, the reaction from a perceived loss – whether it be pleasure or pain – will be exaggerated indiscriminately. In other words, Possession Losses always intesify the positive or negative changes experienced.

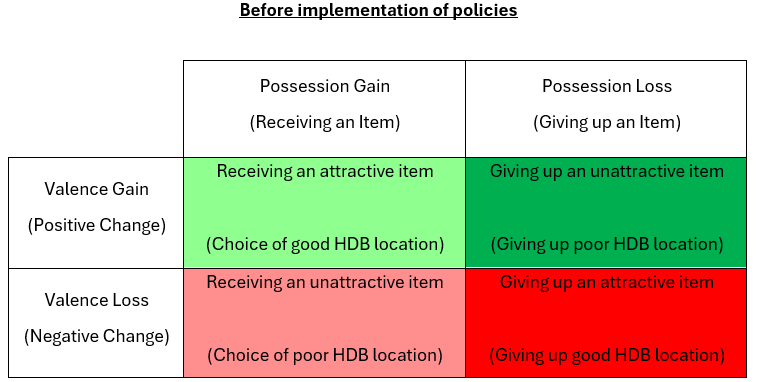

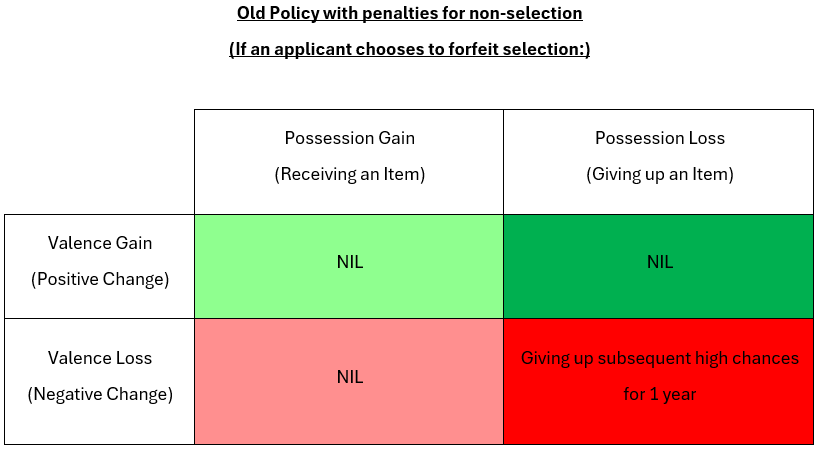

Fig. 2 – Cognitive decision-making table by relative weightage before implementation of policies. Fig. 2 maps out the cognitive decision-making process without any policy intervention, with dark green representing the most pleasurable decision and dark red representing the most painful decision based on Posession Loss Aversion (PLA) and Valence Loss Aversion (VLA) Theory which were postulated by Tvesky and Kahneman7. Applying these theories to the non-selection rates, it becomes clear that applicants experience most pleasure giving up HDB units in poor locations, which may lead to a high non-selection rates in general.

To combat this effect, policies with penalties were introduced to “nudge” citizen behaviour in an attempt to reduce non-selection rates. As applicants are penalised and placed into the “Second-timer” category for 1 year, their chances of a successful ballot effectively reduces for a year.

Fig. 3 – Cognitive decision-making table by relative weightage for Policies with Penalties for non-selection. Fig. 3 suggests the cognitive decision-making options when penalties are in effect. Note that there is no real “Possession Gain” in reducing one’s chances of balloting for the HDB flat selection due to the absolute advantage of purchasing a HDB flat in the “First-timer” category as compared to all other modes of purchases in the residential housing market, be it as a “Second-timer”, purchasing in the Resale market, or purchasing a private property, if wait-time was not a factor. In short, “First-timers” receive the highest possibility of securing a highly subsidised and good quality housing unit. With the implementation of PLA through this specific policy, applicants are faced with an extremely painful experience of giving up their subsequent balloting chances with no possible valence gains if they were to forfeit their selection. As applicants attempt to minimise their losses, they may seriously reconsider the situation and choose to proceed with the unit selection despite the selection pool void of their preferred units.

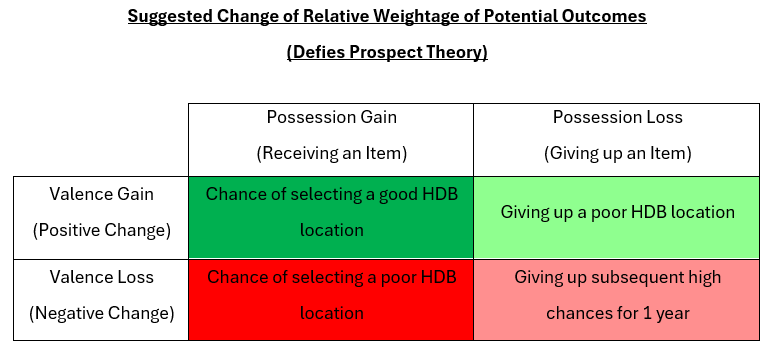

However, sustained high levels of application rates as shown in Fig. 1 suggests a different reality – one where Prospect Theory may no longer be effective. This may be due to a change in the citizens’ relative weightage among these outcomes. Due to the unequal rates of appreciation relating to HDB units, applicants may stand to gain abundantly more by selecting a HDB unit in a superior location. To elaborate, these successful applicants will enjoy the convenience that comes with the prime location, like having established amenities and efficient public transportation within walking range to good views and reduced noise for units at higher levels. Furthermore, they stand to sell their housing unit at a much higher price in future, enabling them to make a larger fortune from this asset appreciation as compared to HDB units in less desirable locations. This leads to a decision-making matrix where the relative weightage of each outcome may have been flipped as suggested in Fig. 4, to make sense of the prolonged high application rates from Year 2021 to Year 2023 in Fig. 1. This defies Prospect Theory’s claim that Possession Loss is always perceived and valued greater than Possession Gains8.

Fig. 4 – Suggested Cognitive decision-making table by relative weightage for Policies with Penalties for non-selection in reality. Fig. 4 proposes an alternative weightage of outcomes where the prospect of selecting a prime HDB location is most pleasurable while the prospect of selecting a poor HDB location is most undesirable. This leaves the outcome of giving up subsequent ballot chances as a “First-timer” on a diminished pain scale. By this proposed logic, applicants rather give up their subsequent chances for either an immediate chance to experience great pleasure by selecting the unit of their choice and make a windfall, or to avoid the great pain of selecting an undesirable HDB unit and be locked in for at least 5 years under the Minimum Occupancy Period (MOP) policy. For readers unfamiliar with this term, MOP is the minimum number of years which the successful applicant must reside in the selected HDB unit before one can sell it on the open market. For this phenomenon to defy the Prospect Theory with redistributed weightages of outcomes, a supplementary behavioural theory under Prospect Theory – namely, Risk Seeking under Loss proposed by Tversky and Kahneman – might be in play to skew the applicants’ perception. In the face of impeding loss, which are the reduced chances of a successful ballot as a “Second-timer”, applicants may double-down and seek risks, gambling everything for a “win” on a “windfall HDB unit”. This is in line with Tversky and Kahneman’s discussion that individuals tend to overweigh the occurrence of small probabilities, encouraging gambling, and become more risk-seeking when facing losses9. This may explain the poor rate of effectiveness of the initial policy before Year 2023.

Rightly so, the government countered this effect in August 2023 with harsher penalties and reduced the desirability of prime locations, resulting in a recalibration of the decision-making matrix. Harsher penalties accentuated the PLA effects. On the other hand, the re-categorising of HDB units based on location desirability seeks to dampen and neutralise the advantages of selecting a prime unit, with longer MOP durations and grant clawbacks upon sale of the unit10. Perhaps, this led to an all-time low applicant rate of 1.1 in the August 2023 ballots which were collated in October 2023 as shown in Fig. 1. Even though the re-categorisation of HDB units would only come into effect in Year 2024, the all-time low applicant rates might have also been influenced by the Recency Effect postulated by Hermann Ebbinghaus in 188511, as then-Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong unveiled this updated re-categorisation policy during his National Day Rally speech in August of that same year12. Thus, having knowledge of these HDB policies designed to level the playing field by the act of removing “windfall”13 opportunities in such close succession, potential applicants’ might have become more Loss Aversive during that short timeframe, leading to a much lower application rate in the BTO sales cycle in October 2023.

Despite the one-off effectiveness of the policies, the application rates are observed to be rising once again after October 2023. Though Fig. 1 only represents the application rates from the Kallang Whampoa planning area, readers should be cognisant that application rates for HDB units at desirable locations are increasing once again. This may be due to the diminished Recency Effect as more time has passed since those policy announcements. More disturbingly, it might reflect our society’s underlying assumptions of the local housing market and a blind faith in the appreciation of the land-value of these HDB BTO units to the point where no intensity of nudging may prevent us Singaporeans from betting our only chip in this all-in poker game just for a slim chance to hit the government-sanctioned housing jackpot.

Nonetheless, this essay recognises the limitation of the theories proposed to make sense of the data. The mechanisms within the housing market are complexly interwoven with a multitude of considerations which are not discussed in this essay. Those include housing factors like supply-side factors and wait-time (to build and to serve out one’s MOP) to a broader socio-political and socio-economical landscape. The policies’ effectiveness likely stems from a confluence of these factors, each applying varying degrees of pressure to the decision-matrix, rather than by psychological theory alone. The key idea is that although phenomena may be explained using psychology theories, this may not directly translate to it being the sole variable in controlling citizen behaviour. Therefore, on a city-scale, it is paramount that policymakers do not fall into the trap of “behavioural determinism fallacy”, where complex urban issues are oversimplified and factors influencing behaviour, like those mentioned in Prospect Theory, are misunderstood as absolute tools to determine behavioural outcomes.

However, there is a noticeable trend of policies employing Prospect Theory – targeting the pain from losing one’s money – which earned Singapore the moniker ‘A “Fine” City’. These are also evident in law enforcement, particularly with smoking and vaping, and housing stamp duties where both buyers and sellers may need to pay a percentage of the transaction to the government as a means to “cool” the housing market. This observation may open further discussions on the effectiveness of Prospect Theory through policies implemented in Singapore, an analysis of such a culture revolving around the fear and avoidance of loss and further applications in the policymaking landscape in Singapore.

-

For every 1 unit available, there were 1.1 applicants contesting. ↩

-

Housing & Development Board. “Keeping Public Housing Accessible for Singaporeans.” Press release, March 2, 2023. Accessed November 3, 2025. https://www.hdb.gov.sg/about-us/news-and-publications/press-releases/02032023-Keeping-Public-Housing-Accessible-for-Singaporeans ↩

-

Housing & Development Board. “Number of Applications Received for 3-room and bigger flats as of 10 Oct 2023” Housing & Development Board, October 10, 2023. Accessed November 3, 2025. https://services2.hdb.gov.sg/webapp/BP13BTOENQWeb/BP13J011BTOOct23.jsp ↩

-

Housing & Development Board. “Keeping Public Housing Accessible for Singaporeans.” Press release, March 2, 2023. Accessed November 3, 2025. https://www.hdb.gov.sg/about-us/news-and-publications/press-releases/02032023-Keeping-Public-Housing-Accessible-for-Singaporeans ↩

-

Brenner, Lyle, Yuval Rottenstreich, Sanjay Sood, and Baler Bilgin. “On the Psychology of Loss Aversion: Possession, Valence, and Reversals of the Endowment Effect.” Journal of Consumer Research 34, no. 3 (October 2007): 369. https://doi.org/10.1086/518545 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid, 370. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk.” Econometrica 47, no. 2 (1979): 286. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185. ↩

-

Housing & Development Board. “Standard Plus and Prime Housing Models.” Accessed November 3, 2025. https://www.hdb.gov.sg/cs/infoweb/residential/buying-a-flat/finding-a-flat/standard-plus-and-prime-housing-models ↩

-

Jaap M. J. Murre and Joeri Dros, “Replication and Analysis of Ebbinghaus’ Forgetting Curve,” PLOS ONE 10, no. 7 (2015): 1, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120644 ↩

-

Yufeng Kok, “NDR 2023: New public housing framework needed to ensure affordability, fairness and good social mix,” The Straits Times, August 20, 2023. Accessed November 7, 2025. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/politics/ndr-2023-new-public-housing-framework-needed-to-ensure-affordability-fairness-and-good-social-mix ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

-

Can the Draft Master Plan 2025 make a Good City in Singapore?

#Urban Planning #Social-spatial ThinkingCan the Draft Master Plan 2025 make a Good City in Singapore?#Urban Planning #Social-spatial ThinkingThe Draft Master Plan 2025 (DMP2025) outlines 4 main themes to guide land use plans. These themes are embedded in the Regional Plans as tangible proposals presented in the exhibition. The DMP2025 shall be evaluated holistically based on what it represents and seeks to achieve, along with its planned execution of these overarching ideas through specific examples provided in the Regional Plans. Theoretically, it will be hard to deny that the DMP2025 would make a Good City in Singapore. Afterall, it meets most of the 5 basic criteria constituting “Good City Form”1. However, a “Good City” is not solely defined by Kevin Lynch’s “Good City Form” but should also encompass values that hold importance to the inhabitants of the specific city.

Singapore is textbook when it comes to planning and executing theoretical concepts – efficient and precise. This holds true for DMP2025 as well. According to Lynch, “vitality”, “sense”, “fit”, “access” and “control” are characteristics of “Good City Form”, required for the city to perform competently2. This paper will briefly describe how the DMP2025 meets some of the “Good City Form” criteria before discussing the value-centric approach in detail.

With a focus on a “happy, healthy city”, DMP2025 supports higher-ordered human capabilities, emphasising the importance of good physical and mental health. The plan proposes for more inclusive neighbourhoods which supports sport activities, with further attention towards suitable housing and neighbourhoods for a diverse population, including the aging community. With this example, vitality, sense and fit are achieved. This is one of the many examples within DMP2025 which meets Lynch’s “Good City Form” criteria.

Going beyond the criteria of “Good City Form”, DMP2025 attempts to wrangle with and align its planning values with the changing value-matrix of the people on the ground. Firstly, DMP2025 is people centric. Whether it be from the “Shaping a Happy, Healthy City” theme, or specific Regional Plans like the new Central Manpower Base (CMPB) where the facility is not solely bureaucratic in nature, but a community hub to provide amenities and promote an active lifestyle, these initiatives’ priority seems to be “putting people first”.

Secondly, DMP2025 strives for equity on top of its people centric approach. A slew of proposals from inclusive and well-connected land transport systems to accessible amenities attempts to bridge all individuals to supportive communities and affordable amenities, with programmes such as the “Hawker Centres Upgrading Programme 2.0”.

Thirdly, DMP2025 is legacy and continuity driven. It recognises the past as an important construct to Singapore’s identity, as DMP2025 tries to adaptively reuse prominent spaces within our built-environment, like Golden Mile Complex, and revive a collection of connections in the “Identity Corridor” plan. DMP2025 also looks towards the future in its planning process, prioritising sustainable and resilient approaches to planning our way of life. With plans to “support growth in a net-zero city” and climate-responsive urban design to cool down public spaces using passive design and protect the island from floods, the DMP2025’s intentions are clear – it protects legacy and plans for continuity.

Finally, DMP2025 plans for economic growth through attempts to identify unused or undertilised spaces, revitalising them to ensure that the potential of each space is maximally realised. An example would be the revitalisation of the Downtown Core. By seeding residential neighbourhoods into this business district, not only can it help with dispersing some density from crowded neighbourhoods outside business hours and during the weekends, it also encouages some form of economic activity beyond working hours when the Downtown Core becomes more mixed-use. Other initiatives support businesses with more flexibility, like the Woodlands Experimental Zone and the Enterprise District piloted at Punggol Digital District.

Through digesting the immense plans the DMP2025 has to offer for Singapore, I notice that there has been a shift in the priorities of Singapore’s planning values, as if responding towards the changing socio-political landscape in Singapore. Throughout the years, there has been an outspoken rhetoric to place the common people first, instead of dehumanising individuals into mere numbers for economic productivity metrics. It feels as if the DMP2025 is a direct response to this outcry. While recognising that planning for economic growth is still required, the entire narrative seems to direct the spotlight onto “the people” and their lived experiences. The Themes anchor this value, and Regional Planning projects operationalise it. In contrast, the objective of economic growth seems to fade into the background – never forgotten, but not celebrated in the narrative. Furthermore, as the city becomes increasingly diverse with the growing influx of foreigners, the city’s inhabitants seek a grounded identity while pursuing survival and continuity. Again, the DMP2025 responds aptly with its urban planning solutions.

It is through this dialogic dance between the people’s rhetoric and the planning proposals that I conclude that the DMP2025 makes a “Good City” in Singapore. DMP2025 identifies the ever-changing value-matrix by listening and distils it into a unique composition of planning solutions which adapts to and reinforces the “will of the people”.

Having said that, there lies two wicked problems which exists in DMP2025, grounded in Lynch’s meta-criteria. From the point of “efficiency”, which balances cost-benefit across values for maintaining the settlement3, a stronger emphasis on “people” over economic growth may be detrimental to a small and resource-scarce city like Singapore, whose formula of success is rooted in the constant pursuit of economic growth. Similarly, the meta-criterion of “justice”, which distributes cost-benefits across people4, may be de-valued as the burden of actualising the resource-heavy DMP2025 in the coming 15 years is most likely borne by the bulk of sandwiched middle-class taxpayers. Furthermore, as DMP2025 transforms Singapore into a better city, it would also inevitably increase cost of living and overcrowding as it attracts further influx of foreign businesses and individuals. To this, I have no real solution, except to cynically concede that any plan which makes a city good, may also inexorably hasten its own demise.

-

Reading Urban Landscapes: Modern Planning influence in Bidadari & Boon Keng